In today’s art world, many artworks and exhibitions rely heavily on texts to guide their audience. When one reads the blurb accompanying a book or a film, it consists of a brief synopsis so the consumer can gather whether they are interested in engaging with the material or not. In visual art, however, one has already consumed the content and can then read a short analysis to deepen one’s perception of the work.

Wall texts in exhibitions vary in length and depth of analysis. In the 59th edition of the Venice Biennale, the wall texts are detailed and unauthorized. The texts of the international art exhibition, Milk of Dreams, curated by Cecilia Alemani, sparked my interest as they altered my perception and understanding of the works themselves.

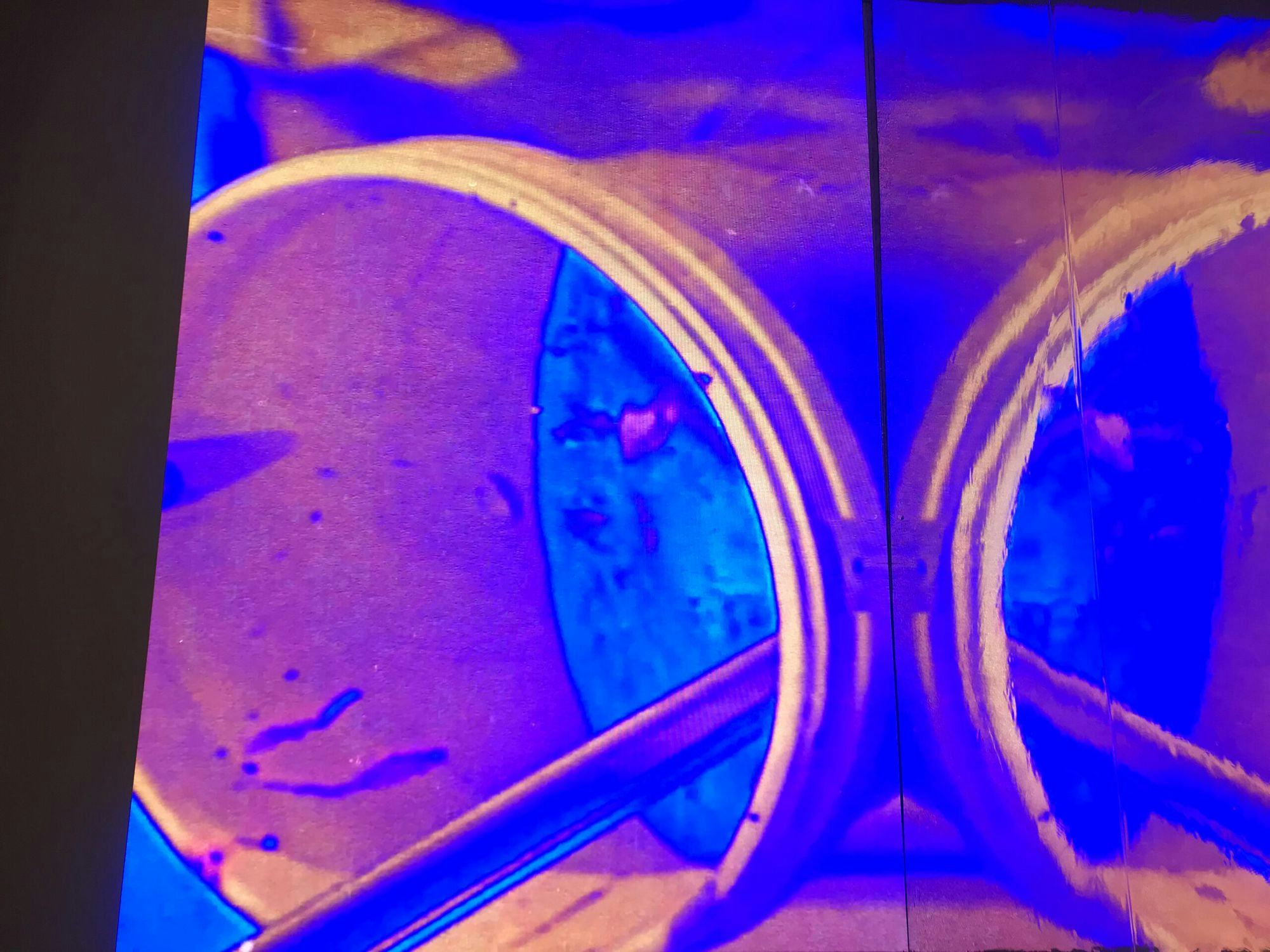

P. Staff, On Venus, 2019.

In today’s art world, many artworks and exhibitions rely heavily on texts to guide their audience. When one reads the blurb accompanying a book or a film, it consists of a brief synopsis so the consumer can gather whether they are interested in engaging with the material or not. In visual art, however, one has already consumed the content and can then read a short analysis to deepen one’s perception of the work.

Wall texts in exhibitions vary in length and depth of analysis. In the 59th edition of the Venice Biennale, the wall texts are detailed and unauthorized. The texts of the international art exhibition, Milk of Dreams, curated by Cecilia Alemani, sparked my interest as they altered my perception and understanding of the works themselves.

Marianna Simnett, The Severed Tail, 2022.

One of the provocateurs of this year’s biennale, P. Staff, exhibits in Giardini their video-piece On Venus (2019). At the entrance there is a warning, like a delicate exit sign in beige, with the words: “Sensitive content//strobe lights” written on it. I enter through a curtain into a neon-colored strobe light mania. The lights and bizarre colors of the image distort it to a point where the eyes often can’t fully grasp what they see.

One might walk in at a time where the imagery is clear and get the context right away, or one might be lost for a while. Eventually the colorful blinking picture reveals a cow’s body being sawn in half. One sees close-ups of tools or longshots of the slaughterhouse, close-ups of chicken’s claws or cow’s ears, and longshots of various bodies. The distortion of the image shields the audience, unlike clean-cut videos of slaughter, with the blood spilling in neon pink, blue or green, it does not invoke the same feeling of horror. The distorted image also hides the look of fear in the eyes of the animals. Unlike many head-on vegan documentaries, the video-piece does not fall into the category of emotional pornography since it shields the audience from the horrors of imagery. But this same distortion of neon and strobe-lights adds to the discomfort of the viewer through other means. It is not an easy watch. The video becomes uncanny, striking the audience as both brutally real and alien. The political issue at hand is the distance we create between human and animal, our ideological perspective; the video plays with this distance by distorting our visual perspective. The video thus works as an uncomfortable reminder to acknowledge the distortion of thought with its visual distortion, without playing with the emotions of the audience. It is both simple and powerful.

-2021-2000x1333.jpg&w=2048&q=80)

Zheng Bo, Le Sacre du printemps (Tandvärkstallen), 2021.

In Arsenale, one of the screening rooms has a furry tail sticking out from its curtains: The Severed Tail (2022) by Marianna Simnett. There isn’t a warning sign in sight, but perhaps the tail is a warning sign in itself. Ironically, the tail lures in children roaming exhibitions with their guardians. I step into a foul-smelling room. The smell does not serve the video content. The video is sexual in nature, while it plays with power dynamics and unsettling images such as puking up roe which is to be inserted into another’s belly button that opens up like a flesh wound, making me think the smell is a part of the piece and perhaps the artist put something that is gradually rotting into this furry tail.

The entire room is covered in fluffy faux fur, and guests casually lie on the tail while viewing.The aesthetics of the room, in addition to the film’s narrative (a Piglet-looking protagonist, and other animal-humans in a sexually aggressive plot) instantly makes many viewers associate the film with furries. In this day and age, we, the art-orientated liberals, celebrate sexual liberation in all forms of kinks and orientations. So I failed to understand why the artist (given that the smell is intentional) would want to associate a piece that gives a platform to a nieché sexual orientation with “something rotten.” I search the curatorial text for answers. The video work is a feminist story of a female/femme piglet on a “cathartic odyssey of transformation and desire.” I figure the smell is most likely as unintentional as the work resembling a tale of furries.

Before entering another screening room, I read a subtle “sensitive content” warning and walked into Le Sacre du printemps (Tandvärkstallen, 2021) by Zheng Bo. The screen shows naked people amongst trees, and I wonder if it only takes nudity in nature to qualify for a warning sign. The video progresses into people moaning and rubbing up against trees. I’m both lost and unbothered. In its vagueness, the video is open to multiple political interpretations; it could be taking inspiration from the hippie movement and environmentalist tree-huggers while also giving a platform to a minority of sexual orientation. Perhaps this is the intent and genius of the work, but I’m not sure, so I read the text.

P. Staff, On Venus, 2019. Photograph: David Levene

The text is drowning in artspeak phrases like:

“Eco-sexual curiosities.”

“Post-human vibrancy.”

“[The artist] is committed to all-inclusive, multi-species relationships” and “[partakes in] daily rituals that focus on interspecies care.”

The idea that plants and humans share a bond not cultivated by most is more thrilling than the work itself, and my shallow double-interpretation of the piece wasn’t far off, although it lacks the vocabulary.

Once I get home, I read On Venus’s curatorial text to reaffirm my political reading of the work: “necropolitics” “affect theory” “Staff’s examination of the exchange between bodies, ecosystems, and institutions from a queer and trans perspective”. I re-read the last four words. Of course. Animal abuse has long been a popular depiction of our society’s mistreatment of human minorities. The point remains the same; we allow abuse to various bodies because our collective empathy excludes “otherness.” However, with this new information, the fragility and absurdity of the body become more apparent in the video.

In my perception of On Venus, I missed the queer and trans aspects but still grasped the emotions and the ideology within the work. The video stands on its own as a very powerful political artwork, and accompanied by both the curational text and articles, my perception is deepened. In comparison, my loose interpretation of Le Sacre du printemps was uninspired but close enough. However, the curational text sparked my interest more in the theory behind the work than in the actual work itself; A feeling I think many people are familiar with after leaving an art exhibition. My horrible misinterpretation of The Severed Tail made me feel the fault was with the work itself. The curational text may have corrected the misunderstanding but did not salvage the work. In conclusion, if enraptured by a piece, I seek out written information on it. Yet a written explanation can’t make me gain interest in the piece itself – if the idea is better than the work itself, or the work can’t speak for itself, perhaps the most fitting medium for the topic, for the moment, is written theory. Even though in these three examples the wall texts made me better understand the works, I still am of the opinion that the texts of this exhibition are over explanatory.

In these examples, the artworks themselves are politically driven. Therefore, the curational texts do not feel as if politics or ideologies are forced onto the work for added value. Nevertheless, there is undeniably an “emperor’s new clothes” aspect to many wall texts. The texts can give off the impression that the fault lies not in the work itself but in the viewer’s perception of it – the viewer’s intellect is at fault for “not getting it.”

Now, I understand the appeal of politically heavy exhibition texts. Many artists and art-lovers struggle with the meaning of art and seek refuge in artspeak. They latch on to meaning found in philosophy or politics. Ironically, this political quest often praising inclusivity is expressed within the exclusionary nature of artspeak. Not to mention, since the artworld is heavily tied to the market, its compulsion to include political topics often leads to artwork representing ‘battles that have been won.’ Perhaps it is a worthy cause for art to celebrate the once radical, now socially acceptable ideologies, and art can be powerful in reexamining our histories, but I’d also like to address a different approach to this urge within the artworld to deal with politics.

At a lecture hosted by the biennale, Sebastiano Maffettone, professor of Political Philosophy, spoke on posthumanism. He began by saying that art has, throughout the years, been ahead of philosophy in predicting future ideologies, mainly because art explores other realms and senses than logic. Maffettone found the statement so obvious that I bought it immediately as well. One example he took is this year’s curated exhibition and its focus on surrealism, a cultural movement in art and literature that flourished in the years between the world wars, which is now being linked with philosophies on posthumanism. But Maffettone’s statement left me with an eerie feeling. The feeling arose from curatorial statements already analyzing and giving meaning to their work, not to be later understood logically but immediately inseparable from “its concept.” Since a lot of art today is rooted in concepts and political agendas, it leaves little room to explore alternative realms and senses opposed to logic and understood by emotions. If future philosophies are to build on our current art scene, they will be working with pre-determined meanings. On top of this, political change usually comes after philosophical enlightenment. If my calculations are correct, then; first comes art, then philosophy, and last comes a change of politics.

With all this being said, I’d like to encourage a step back from art being bound to curatorial text and verbalized meaning. Art can have meaning, even if its meaning is not immediately understood. I want more art to break free from pre-determined “political concepts” and seek to be philosophically understood later. Art that, rather than reflecting on societal change, causes it.

-icelandic-pavilion-2000x2667.jpg&w=2048&q=80)