Now on view at the Reykjavik Art Museum – Hafnarhús are three exhibitions. A video installation by Sara Björnsdóttir, a noteworthy exhibition of drawings by Dan Perjovschi and the one I will discuss here: a group exhibition titled Power of Passage, curated by Hafþór Yngvason, director of the museum.

The works in Power of Passage are chosen because of the way the artists use process and time, and because of the assumed act of the artists letting go of control over their works and letting coincidence take over. As is stated in the wall text: “All of the artworks presented involve progression and change. They are the outcome of impersonal and indeterminate processes that the artists use to transform their materials from one state into another. The final forms the works take are unpredictable, as the artists allow the dynamic chemical reactions of the materials to work on their own, largely without interference of the artist’s own hands.” There is definitely a methodological similarity between the works. Time is one of the materials used in the crystallizing of salt, the cracking of paint, the colouring of rust and the seeping of light, for instance. I would not for a second, however, dare to think that the artists are not creating their own works and maintaining control over them, despite using time and transition in the process. They use time and the transition of materials as elements to work with. Experiments are made, the qualities of materials and their transformations explored. The stage is set, the materials arranged, according to a vision, a concept or intuition, and then time and transformation play their part, with faith, trust and determination. The artist then deems the work either worthy or not, as with any other way of making art. It is always necessary to trust the process, whether or not a human hand is involved the whole time. Of course making art is not just about labour, decisions and editing count just as much. And besides, you can hardly ever perfectly control anything anyway.

Jóhann Eyfells, Power of Passage, Reykjavík Art Museum 2012.

The centrepiece of the show is a “collapsion” by Jóhann Eyfells; a huge cloth, coloured by the rust of metals that were layed on top of the fabric outside in the mud and left there until there were marks in the cloth. The piece, created in the 80s, is installed in a zig-zag through the gallery. This use of transition in materials in the work, i.e. how the metal leaves its marks on the cloth, is then the structure for the remainder of the show.

Orbiting around Jóhann Eyfells’ gigantic centrepiece are subtle works by four mid-career female artists:

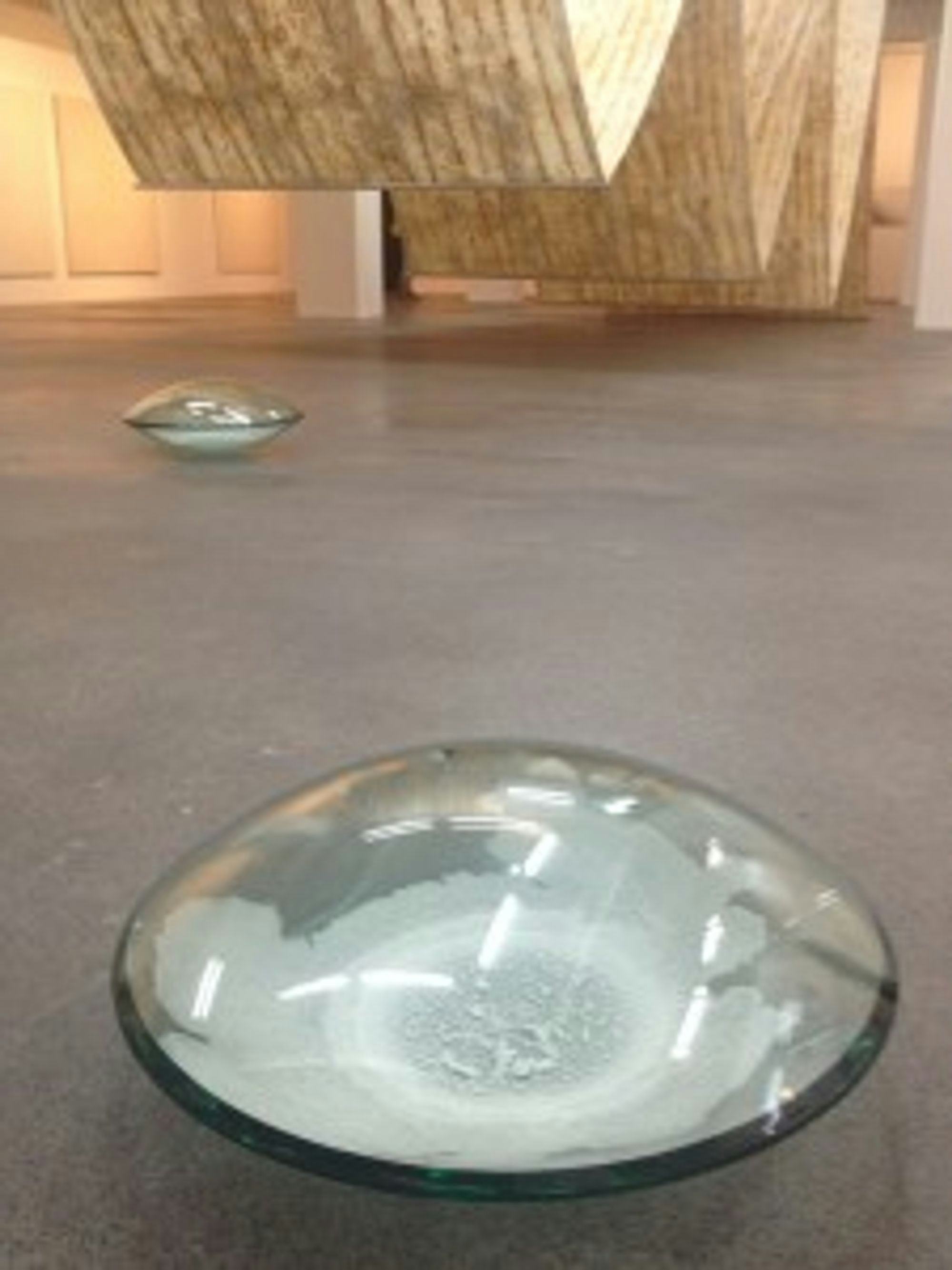

Ragna Róbertsdóttir, Power of Passage, Reykjavík Art Museum 2012.

Crystalized salt formations, displayed both inside glass capsules on the floor and affixed to paper and framed on the wall, are works by Ragna Róbertsdóttir. The works ooze delicacy, both in the fragile material that has a feeling of possibly cracking or melting any minute, in the moderate scale and in the almost transparent colour effect of the salt on glass and white paper.

Harpa Árnadóttir, Power of Passage, Reykjavík Art Museum 2012.

Harpa Árnadóttir’s works are big canvases layered with white pigment and glue, causing the white surface to crack from the drying process of the glue. The result is a surface patterned with cracks, again bringing up thoughts of time, transition and fragility.

Sólveig Aðalsteinsdóttir, Power of Passage, Reykjavík Art Museum 2012.

Sólveig Aðalsteinsdóttir has black and white photographs, developed from films exposed by light seeping into a darkened room. She does not use a traditional camera or lens and the curator’s text states that the important tools a photographer has to determine the outcome of his works, shutter speed and aperture, “play no role in the outcome”. On the contrary, I believe that they are the very elements that do mostly control the outcome of Aðalsteinsdóttir’s works. The cracks that allow light to seep in, and the time she allows the film to be exposed to it, are vital to the outcome. She is playing with light, which, in addition, gives the works painterly qualities. Despite the fact that “she is clearly not trying to ‘capture’ the optical images of physical objects but to capture the time involved,” as the curator correctly states in his text, she is not only capturing time, she is also using light, darkness, time and film to create an image.

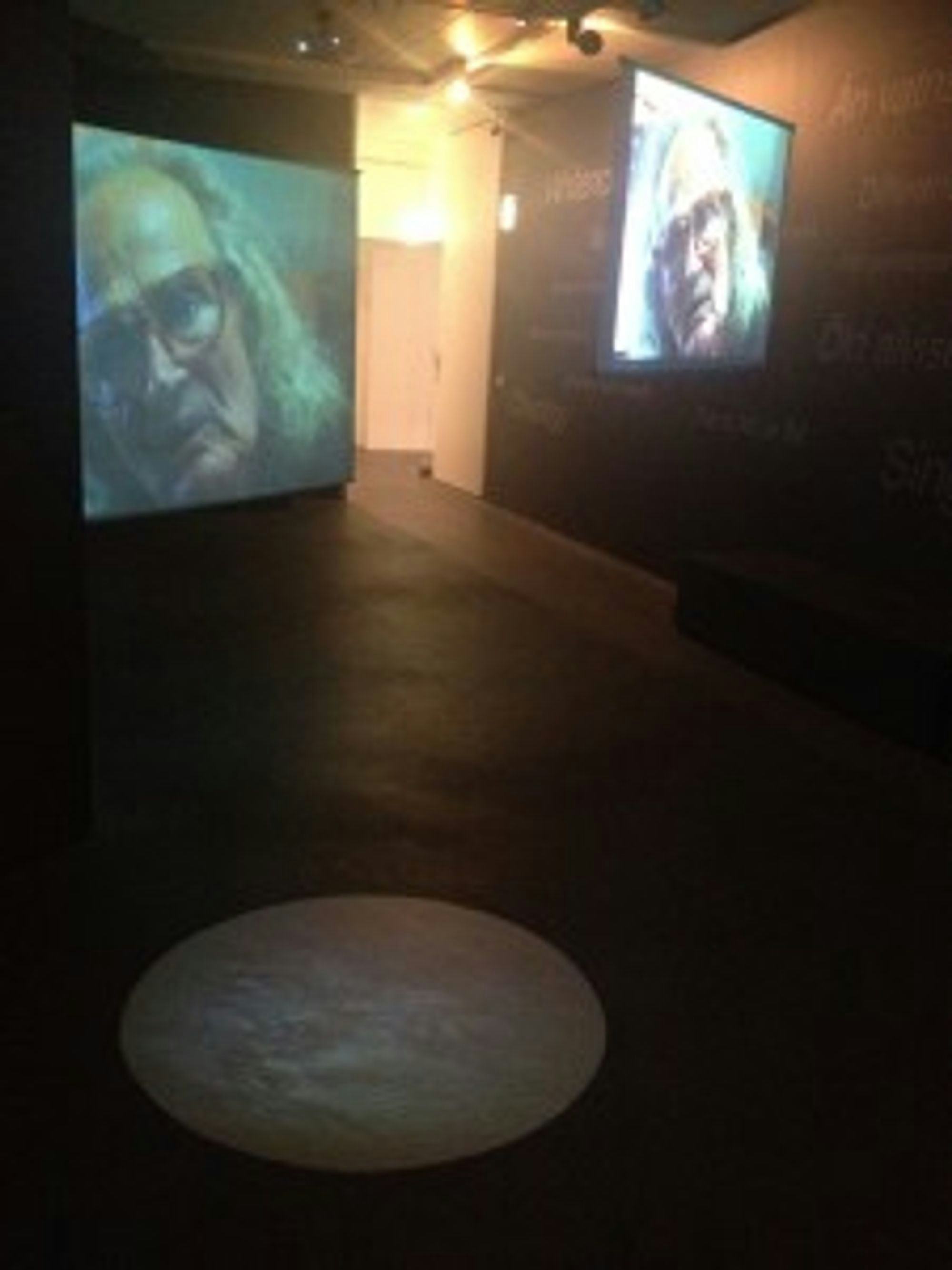

Guðrún Einarsdóttir, Power of Passage, Reykjavík Art Museum 2012.

Paintings by Guðrún Einarsdóttir are the only works with colour, except for Eyfells’ rusty red. She uses traditional painting materials, oil, pigments and solvents, but experiments with types and quantities, and changes the way paint is usually made to dry. The up-to-14-months’ drying time sometimes causes the materials to circle up, contract and make formations, reminiscent of nature. The works are of course affected by similiar elements to those that can affect nature, namely time and transition, and the link to nature seems intentional, judging by the title of the ongoing series, Material Landscape Project.

Most of the works are good and the exhibition is well installed, but I wonder if putting these works together benefits any of them. It establishes that artists work with process, which can be interesting to address. It is of course old news, as the curator points out in the catalogue, where connections are made to Man Ray’s 1920 photograph of Duchamp’s Large Glass, which he left to collect dust for a year, known as Dust Breeding (Duchamp’s Large Glass with Dust Notes). Duchamp then wiped the glass mostly clean but selected areas that he left covered with dust and permanently affixed it to the glass. As this almost century-old example suggests, sure time and coincidence play a role, but it also reminds us that the artist’s decisions and editing are pivotal.

Finally, it has to be mentioned that an entire gallery was taken up for an installation of a documentary about Jóhann Eyfells by Þór Elís Pálsson. Sadly, I have no idea whether the documentary was good. Even though I was very interested in it and wanted to listen to Eyfells I just could not focus on the screens because of the distracting installation. All I could think of was “what is this?”. Thoughts about booths promoting nature to tourists prevailed and disturbed me, and then I had to surrender to my weaknesses; my attention span had failed me. I just hope it comes out on DVD.

Anyway, to wrap things up: time, impermanence, fragility, process… personally, I am a fan. But the nature of these subjects is so delicate that combining many different works dealing with them so directly, even similarly, in my opinion does not make the case stronger. Instead, it somehow diminishes the potentially powerful, subtle effect.

-icelandic-pavilion-2000x2667.jpg&w=2048&q=80)