Hulda Rós Guðnadóttir on art practice as research.

Hulda Rós Guðnadóttir is a Berlin based Icelandic artist and the initiator of the art project Keep Frozen. The project has taken place in Germany as well as in Iceland. We met up with her during the project’s symposium in Reykjavik called Reclaimed Landscapes in February. Its aim was to provide a forum for multi-disciplinary dialogues about art practice as research and I was keen to learn more about it.

You’ve been working on the Keep Frozen Projects, in which you shine a light upon the experience of being a labourer today in the fishing industries, since spring 2010. Where does the name of the project originate from and is there a story behind it?

The title of the project originates in the inscription on the boxes used in the freezer trawler Vigri, which is unloaded about once a month in the Reykjavik midtown harbour. Vigri is the star of a documentary I have been working on this entire time, which poetically addresses the task of manually unloading of the frozen cargo of fish fillets packed in those boxes. The boxes contain great value and it is important to keep the content frozen, thus every single box has this label. They should be kept frozen at -30̊ C, which is also the temperature at work for those men.

It was my film producer Helga Rakel Rafnsdóttir that suggested the title as a working title for the film and as we were using it I started to see all kinds of meanings in the title that were relevant to what I have been doing and thinking with the research project as a whole. I started by digging into memories of my past and ‘living memory’ within my family, and have had to ask myself time and again throughout the process whether I was being nostalgic, and what nostalgia is. Thus Keep Frozen. Keep Frozen can also refer to transportation methods, but a lot of goods are kept frozen during transportation, and this demands great amount of energy. The transport of goods has political, ecological, historical and even oceanographic dimensions and is a very relevant topic today. There has never been a point in history in which more products were being moved around the globe; and often in very absurd directions. During my trip to Reykjavik, for the exhibition at ASI and the Keep Frozen Projects symposium at the Icelandic Art Academy, I ate tuna that had been transported, probably frozen, all the way from the fish markets of Taiwan, and calamari that was also imported, from Spain. The staff of the restaurants had no idea where the food they were selling came from, although both restaurants market themselves as selling ‘Iceland authenticity’, in line with the ‘local living’ trend.

It can also refer to the idea of the masculinity of the working class, where the identity of the male is often allocated to the body, and less to spoken words or the expression of feelings or opinions.

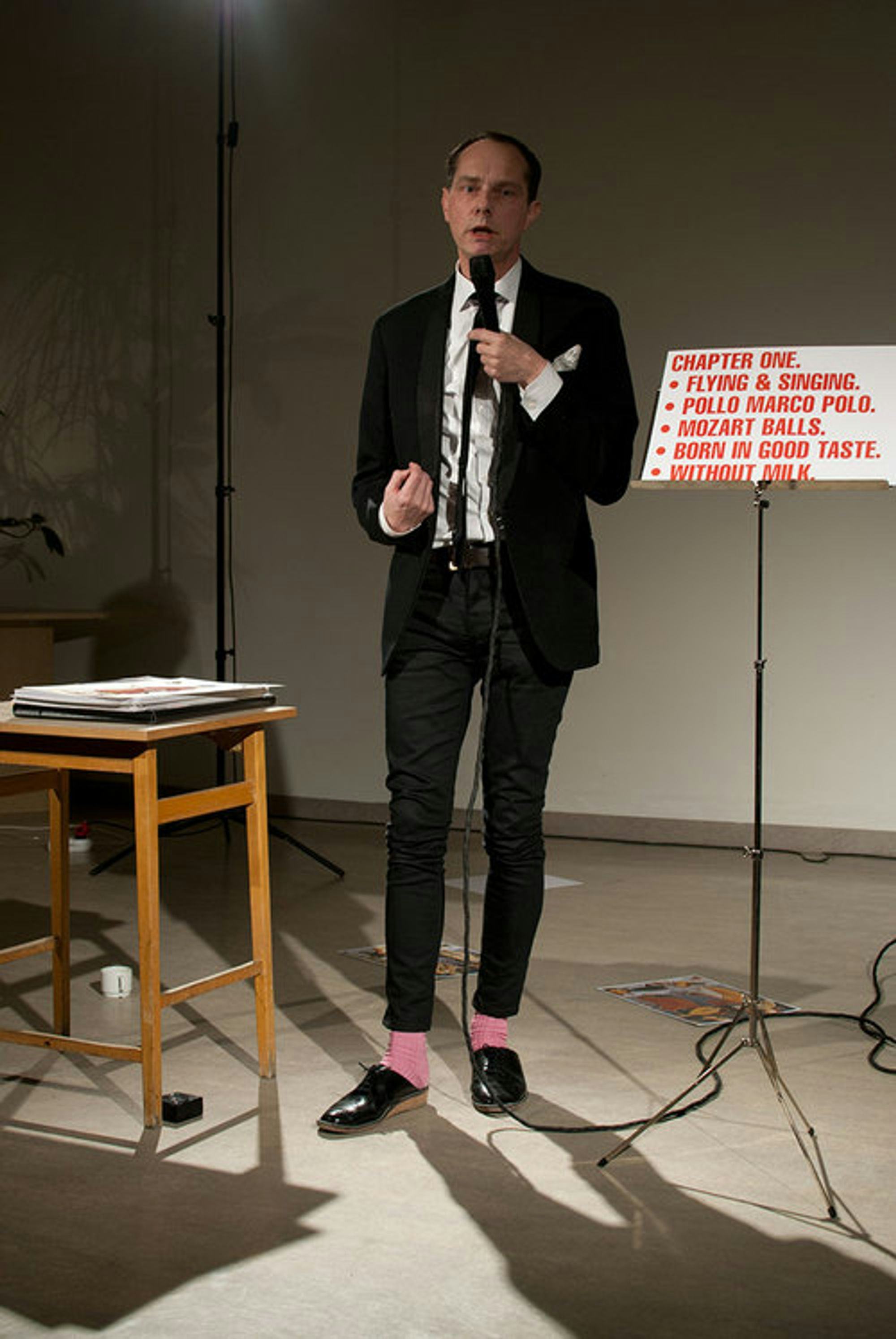

Olof Olsson ‘Driving the Blues Away’. Photo: Hulda Rós Guðnadóttir

You have previously spoken about the main goal of your Keep Frozen project being to highlight some of the hidden work, and sometimes manual labour, that happens every day in our society. Can you explain this focal point, the reasons and importance behind it?

To continue with the thread of the previous answer, the working class male has been marginalised as a voice in our capitalistic society, with the effect of his identity being relegated to the body. Once a hero of other ideological systems, like communism, the working class male is thought of in very simplistic terms in elitist capitalism. When you look back in recent history, you can clearly recognise a greater variety of images and identities of the uneducated working class, as a group that also included people with great creative or intellectual capacities and valuable perspectives, who had chosen to work manually. Today when the media is looking for a voice to address an issue, it turns to those who have either cultural or financial capital, the organisers, CEOs, marketing people, entrepreneurs, the university educated classes, but not to those who are actually doing the fundamental manual tasks that are the pillars of everyday life, and witness it on ‘ground level’, or more precisely, perform it. This projection affects the working class, who eventually took on this identity as their own: the silent worker only capable of selling his body. It is not good when a large part of the population is silenced and its identity is oversimplified. It can lead to aggression or to frustrated people becoming an easy target for all kinds of political and violent mobilisations. It is worth thinking about that, for example, dock workers are witnesses to the massive transportation of goods and other things legal or illegal that are going around the world. Things that society should not turn a blind eye to. The same can be said about other manual workers. Have you thought about the fact that everything around you has been touched by someone doing manual labour? Nothing would be as it is if no-one was transporting stuff from one place to the other. You wouldn’t be sitting at your desk reading this blog. The table you are sitting at was moved there by someone. Imagine what these people have seen, what they have witnessed. What is their perspective?

On the issue of ‘these’ people and ‘their’ experiences, it is my opinion that a personal perspective is always a good starting point. It was interesting for me that Hussain Currimbhoy, a programmer at the Sundance Film Festival, noted that what he found important about the Keep Frozen film project was that a ‘working class person was making a film about the working class’. From his perspective, it was unusual and secondly he saw me as a working class person.

Well, I’m glad I’m not guilty of showing ‘the other’. I am the other.

Some of your educational background lies in human anthropology, does that affect your art in any way, its ideology or production?

I guess my interest in society and how it works is what drew me to both anthropology and art. My first university degree was in social/cultural anthropology, with a visual anthropology project as my final project. Together with Tinna Grétarsdóttir I was actually the first student that had a visual project assessed as a degree project on equal terms as if we had written an essay. I’m very proud of that fact, because it started a trend or ‘visual turn’ within the Anthropological Department at the University of Iceland. This turn was carefully prepared by Sigurjon Baldur Hafsteinsson, then an adjunct professor at the university, and the person who opened my eyes to creative documentaries. The courses which I took there of course helped me greatly. I received tools for my hands and mind that enabled me to independently look at society and culture from a critical perspective—to distance myself—and also to use images as a medium for the expression of my research. It was the early days of my work, which was not yet fully developed, but I gained a valuable point of view, not only when looking at society and culture but also at institutions. That came later when I entered art school. Having been at these two different institutions I realised a lot of the critical discourse and developments going on on each side were lacking in the other. The reason I decided no to pursue an academic career was that I found the tools of anthropology limiting, as well as the space in which the knowledge produced in anthropology was circulated. I found it too elitist, lacking a real effect in society. Also, I was never really so interested in studying ‘the other’, I found it patronizing and archaic. A little later my intuition led me to the conclusion that what was important to me was to be found beyond the analytic tools of academia or explicit knowledge. That there was something important or implicit that could exist and be communicated and understood in that ambiguous space that art allows to just be there, undisturbed, for us to experience together. Art, in my opinion, has much greater potential for a dialogue with the public on different platforms.

Do you believe there is a shift happening towards interdisciplinary research right now, as the symposium last Friday might suggest, that people’s point of view and interest towards new forms of research might be changing? And if yes, why? Or if no, why not?

HR: There is clearly a general shift towards research. Just look at the first research Pavilion at the Venice Biennale last year, organized by the University of the Arts Helsinki. It is clearly linked to academia, and if you look at the schedule: to the doctoral programme.

You ask about interdisciplinarity. Perhaps you are referring to the fact that often the first thing that comes to mind is the interdisciplinary link between visual art and a scientific field of some kind. I personally don’t think that thinking about art as research is something new. We are only rediscovering art as a research tool.

The major motivation for creating the platform of Keep Frozen Projects was to show the multiple ways that artists are and can conduct and show research outside of the academic context or without necessarily linking their work to a scientific discipline. Like I addressed in my presentation in Reykjavik, artistic research is often viewed as something you do for a degree program or, at the very least, inside academia. But like Stefanie Hessler tried to point out, this does not have to be the case. The most interesting art-practice-as-research is happening outside of the academic institution.

Stefanie Hessler, one of the speakers at the symposium, gave a statement saying that peoples’ common knowledge today has expanded to a new level, unlike anything society has seen before. Therefore the public has been developing its expectations towards art in general and what its role should be. What are your thoughts on the matter?

Interesting that you ask that, because this is a point in her lecture that deeply resonates with my own thoughts on why art so often tries to imitate the appearance of science. With Stefanie’s permission, I quote this part of her lecture directly:

‘So I think one could answer that because of the way that the appreciation of science (high, because it is supposed to solve “real” problems, such as global warming) vs. the appreciation of art (low, which is why there is little funding) is so different to what it was during, for instance, the Renaissance, art is trying to emulate formats of science (also because it is pressed into it through the Bologna process). At the same time, art can, and knows it can, produce a very specific type of knowledge that science cannot, and for which the formats of science are perhaps not suited (universities, academic writing etc.). So it is this dilemma that interests me, and which most likely also affects the public’s view and expectations of art.’

I’m very pleased that she is, like me, connecting this to the funding problems we are experiencing in the arts. It is a very real problem affecting the quality of life of many artists. I would like to add that the funding problems also have to do withwith the fact that the current hyper-emphasis on the value of art in terms of capital and the art market causes the public to no longer understand the relevance of art for everyday life. By shifting the perspective and looking at art as a research tool rather than a tool to make objects to sell, I think the public will reclaim art as a means of empowerment, and will no longer be so easily manipulated by power-hungry politicians. So it is a real problem. Politicians use art as a manifestation of the enemy they so badly need for voters to back them, because their experts have recognised art as a vulnerable target. In a neoliberal climate, it has been thought of as a logical method to heighten the reputation of visual art by linking it to luxury products. I find this very misguided. Why should the public want to fund the production of luxury products? I think that by looking back in history we can learn something about this mechanism. Much like Stefanie, during our symposium in Leipzig the Danish philosopher Sören Kjörup reflected on how during the Renaissance people were looking for a method of raising the status of visual arts vs. crafts by connecting visual arts to science. Art was no longer to be viewed as a craft, but something higher instead, and so they took the universities as a model. Something like a ‘high intellectual position’-by-association method. What was going on in the universities of that time was a turn towards the classical, discoveries of old texts, and a lot of the words and obsessions we use/have in visual arts come from that era. Composition for example. The reason we attach such importance to the composition of an image is because of the Renaissance link of visual art to universities at that time. Images had to be composed. And Sören, like Stefanie, pointed out that we are doing the same thing today. We are looking again to the universities, which—as Stefanie points —out receive ‘high appreciation’.

We should never forget that if we let art be solely the concern of the art market, it will be the exclusive property of the rich in this world, and the public will have to go without this very substantial tool of empowerment and reflection, a tool to think critically together as a society. This of course goes against what so many have been fighting for: to shift from the feudal system to democracy and creative and enriching lives for the masses. It is a part of democratic fair society that we want to live in, that instead of the church or the rich being the patron of artists, this is done communally by society through public art funding. That is one way of distributing power or the capacity to be free, critical, and in control of who you are and how you affect the world. This of course is a population that is difficult to manipulate, or use for the purposes of individuals who aspire to power and wealth for themselves; thus art and artists are a popular target to undermine.

Stefanie Hessler. Photo: Andrea Aðalsteinsdóttir

When you spoke at the conference, you mentioned that the results of artistic research don’t always have to be usable in any way for them to be considered valid, which certainly divides them in many ways from research within other fields. By your definition, what conditions need to be fulfilled in order for something to be considered research?

Yes. I thought it was necessary to talk about this in the context of art-practice-as-research. What I actually said if I allow myself to quote myself directly:

‘[…] research […] is inherent in art itself, its methods and practices. Research doesn’t need to exist for some commercial innovative end, but for producing new knowledge, even if that knowledge is embodied or experienced and not written down, or analysed.’

And thus we come to the usability issue, which is very much connected to how the public often associates research conducted outside of academia with innovation tied to the making of commercial products. There is a certain expectation that the purpose of research must be to lead to innovation. This is a popular washed out thought that derives from the idea that using the methods of physics, or finding general laws and causalities, is what makes an activity research. It is a very useful method indeed if one wants to produce something, and thus it is an understanding promoted by the innovation industry competing for grants for product development. Something understandable or a concrete, innovated product is at the end of the tunnel. It can be used in a very practical way, often to solve urgent or not so urgent issues or problems. I guess the banana holder was an innovative design at the time, thought to solve an urgent issue. In Iceland we are very familiar with DNA research to produce medicine as a final practical goal. A product that can be sold.

When I talk about embodied or experienced knowledge I talk about the cultivation of the individual or the whole. Art is a type of philosophy or implicit knowledge, which gives space for not only individual artists to embody knowledge but the group or society to think together without an authoritarian voice overriding ambiguous ways to reach understandings. This is very necessary today, when the myth of the truth has been deconstructed and we are aware of the subjective tendencies in knowledge, or the political/ideological connections of the given truth at each moment in history or space. It should be clear by now that knowledge is a phenomenon in constant flux; there is no general rule, only subjective perspectives and individually or group-constructed truths.

Thinking or knowledge production can be done through practice or experience. The body can think when it is doing something, or learn through action or direct experience. I strongly believe that the cultivation of the individual is the prerequisite for the cultivation of society, of the world; of us as humans. Art is something that the individual not only does alone but we as society do together through various platforms of dialogue with the artwork or around the artwork, through experiencing the artwork in a physical, mental and creative way.

To be considered research I think that there needs to be a quest for knowledge involved in art making. What that term ‘knowledge’ means is another story and a subject of debate. There must be an altered perspective and the end of the journey. Fewer blind spots. Like Sören Kjörup said so wisely in an article published in the ‘Routledge Companion to Research’ that inspired me to create the Keep Frozen Projects platform: ‘One of the worst misfortunes that might hit the budding tradition of artistic research is if it should get squeezed into one single format’. There are no specific conditions that need to be fulfilled, only a certain attitude and approach. I think looking at art as research can change the way we generally look at what research is or can be.

Do you believe that common research approaches should be taught within the arts?

Yes, perhaps students should be made aware of or be given real knowledge of the fact that there is no such thing as ‘the scientific method’. It is empowering to realise that there are all kinds of sciences with all kinds of methods. Then perhaps they will start to appreciate that research is inherent in art practice itself. That artists use all kinds of methods to produce knowledge while making art. Perhaps students would realise that it is only a matter of perspective or state of mind when you look at what art is or can be. It would also be empowering to learn the history of academia and its politics. For example how the humanities lost their position of power in the mid 19th century to the technical sciences in explaining how the world works. With it came a claim that all sciences should operate like physics to be valid as science. Perhaps it is still like that in some corners as we actually experienced directly as a response from audience during our own symposiums. Trying to find general laws was the purpose of research. To understand this it is important to look at the historical context. The mid and late 19th century was the time of the Technological Revolution, when industrialization was the driving motor in social change. The much earlier inventions were finally being adapted through technological advancement, clearing the way for manufacturing or production phases. The purpose was clear: To produce objects. It is a legacy that is out of date today and overlooks how different methods create different knowledge.

Stefanie mentions in the quote above that art can produce a very specific type of knowledge that science cannot. Sören was on a similar path during the Leipzig symposium when he pointed out that a central issue to the question of knowledge is the final use of the knowledge that you are in the process of producing or experiencing, sensing or implicitly feeling. We have established that using the methods of physics is useful when you want to produce some product. That is a logical final outcome of looking for causality. But what if you don’t want to produce some product to fill the world? What if we want to do something else in 2016? What if we need different types of knowledge or outcomes or processes? And not for the first time? Neoliberal capitalism has obviously exhausted the world. What is wrong with looking at history to find threads for alternative paths in the future? During the symposium Sören reminded us all of the origin of the word aesthetics in the time before the industrial revolution, in the PHD thesis of Berlin philosopher Baumgarten from 1735. Baumgarten talked about the importance of differentiating between the theory of science that uses logic and on the other hand the field in which he was operating where the knowledge is perceptual, even sensual; and called for another word that could work parallel to the word ‘logic’ to help us understand what we are talking about when we speak of this special kind of knowledge created with art practice, and then he suggested to use the word aesthetics. Fifteen years later his major work Aesthetica was published. So the thought that links art and knowledge or the discussion of the special type of knowledge that art can master is not new, obviously. It just seems to have been set aside. With this in mind, ‘the artistic research turn’ is not about the surfacing of a new understanding but actually a return to an older understanding of what art is and can do. It was during the Romantic area that the link of aesthetics to knowledge started to disappear, because aesthetics started to evolve around the idea of beauty. Baumgarten never mentioned beauty. Now it is time to reclaim his ideas.

Finally, returning to the question of what should be taught in art schools: What I think is most important is that art schools train students to be critically minded, always question the truths presented to them and the way society is constructed. There is no use in ‘teaching’ or lecturing to people that don’t have the fertile ground to digest the input independently. Art schools should be the home of alternative thinking and experiments and also be aware of history and how the understanding of what we are doing has changed and is constantly changing, depending on the ideas of each era. An art school should be a critical force in society. Classes should train thinking to get rid of preconceived ideas. Then the students will be motivated to freely investigate on their own terms.

And ultimately, the students should ask their tutors this vital question: Is it possible to practice art without producing knowledge?

Installation view. Photo: Dennis Helm.

Throughout art history there have been many styles and schools that could be called research based ideologies, for example Bauhaus, the Futurists and the Constructivists. For those interested in learning more about today’s progressive art research within art making, what has influenced you the most in this aspect, any particular artists, styles or people in general?

There is of course the online journal Journal for Artistic Research published by the Society for Artistic Research and the Research Catalogue, which is an online database where you can register and follow other people’s research and post your own. However both are academically linked platforms. RThere are international conferences, regularly held in the Hague in the Netherlands, and the next one is in April. I attended one of them myself some years ago and I encourage all to go that want to learn more about the leading discourse taking place within the academic context. What is interesting for me are the platforms that pop up once in a while and are initiated by artists or museums or other entities outside of academia. Those initiatives seem to be much less accommodating to academic methods such as writing and talking but more dedicated to showing, performing, printing, sculpting, film-making and other methods that artists out there actually apply in their practice. One initiative that is happening right now, for example, is at Le18, an art space initiated by artist Laila Hida in Marrakesh. The program is called KawKaw (means peanut in the Darija language), which unites artists from all five countries of the Maghreb region. They advocate a humoristic approach in breaking the shell in order to reach the grain.

For me it is a matter of looking at those already existing ways of doing things as research. You can find art-practice-as-research everywhere, in museums, galleries, projects spaces. It is only a matter of how you look, hear, see, watch, observe. It is not about a certain style. From the last Venice Biennale the 3-channel video installation ‘Vertigo Sea’ by John Akomfrah is inspiring. It is poetic, haunting and beautiful, scary, bloody, carnal, suggestive, fictional and factual, mythological, personal and collective, with implicit political content based on research and knowledge. It is such a complex work made possible with tremendous support. He is currently showing at the Lisson gallery in London and Arnolfini in Bristol. I’m generally inspired by my contemporary peers. When I lived in Iceland it was the art being shown there that I could experience directly and now when I live in Berlin it is mostly the work by the artists taking part in the scene here. Performance artists and also installation artists. I can be inspired by works that are very different from the way I would show or do works. I like variety and different methods of doing, showing and working. Recently I was at a performance by artist duo Luci Dayhew and Hanne Lippard, who call themselves Luci Lippard and are a all female poetry/drummer collaborative project. I find it stimulating to see what other artists are doing today in alternative spaces and places, and it has most often nothing to do with what I myself am up to. It is nevertheless a cultivating experience for myself and hopefully I project that on the world and into my artwork. I’m not fond of work that obviously only exists in a specific elitist bubble.

Of course I also look outside the Berlin bubble and it is mostly when my colleagues and collaborators lead me to those artists or happen to be the artists, but also during museum and gallery visits during my travels. In connection with my work I have along the way considered the works of such different artists as Allan Sekula, Santiago Sierra, Andrea Fraser, Yto Barrada, Steve McQueen, Sophie Calle, Maya Deren, Jeremy Deller, the Maysles brothers, Tejal Shah, Lawrence Wiener and Buñuel. I named one of my early works after a Buñuel title. Works that are debated, often on the edge of being questionable, alternative stories, imaginative documentation work is something I obviously interested in, institutional critique, interdisciplinary works that are implicitly political, and drag the hidden to the surface with playfulness or humour. I selected the artists Olof Olsson and Dafna Maimon to show at the Keep Frozen Projects symposium. Both apply humour in their works but have very different presentation and working methods. I’m also very inspired by conversations with curators, philosophers, filmmakers and experts in other fields that I have worked with, had conversations with, developed my work with or read texts by. Recent examples from 2015/16 are the filmmakers Dennis Helm, Helga Rakel Rafnsdóttir and Kristján Loðmfjörð, the philosophers Sören Kjörup, Jonatan Habib-Engqvist, and Valur Antonsson; the curator Gudný Guðmundsdóttir; the performance artist and ex-dockworker Hinrik Þór Hinriksson and the musician/visual artist Joseph Marzolla.

Hulda Ros Guðnadottir (IS, DE) is a visual artist, filmmaker and the initiator of the Keep Frozen Projects. She has an MA degree in Interactive Design from Middlesex University (2001) and a BA in Visual Art from Iceland Academy of the Arts (2007) as well as a BA in Cultural Anthropology from the University of Iceland (1997). She has taken part in numerous solo- and group exhibitions and screenings internationally. Guðnadottir has won many awards for her film-making, including Academy Awards (‘Edda’) for best documentary in her native country Iceland.

In conclusion I would like to thank her for taking the time to have a chat and answering my questions.

-icelandic-pavilion-2000x2667.jpg&w=2048&q=80)