In Klængur Gunnarsson’s films, slow and eerie confrontations

with an outside in the landscape focus our attention on liminal moments and places

we might usually ignore. The works are sensitively perceiving the frictions in our

natural world, trying to engage with an otherwise indifferent suburban and cold

environment. Narrators and anonymous characters populate the scenes, treading a

line between the poetic and the political. We talked to Gunnarsson on his working

process, influences and Reykjavik, exploring personal and societal confrontations

with nature.

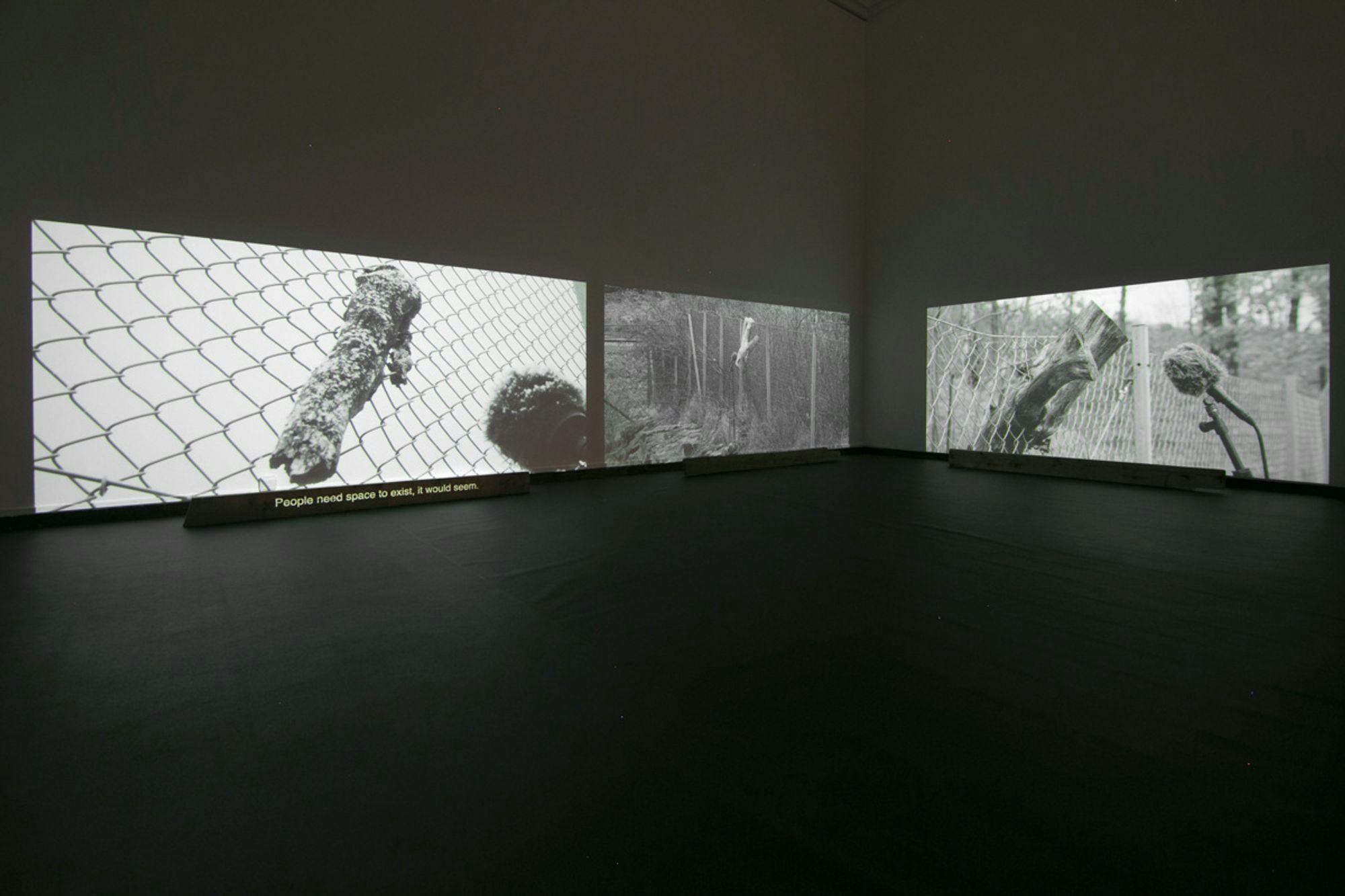

Klængur Gunnarsson: Drift. Gothenburg Konsthall, 2019. 4K video

installation. Courtesy of the artist.

Can you talk us through your artistic

beginnings?

I went to Sweden for the first time after high school

in 2004 to attend a public college, where I studied analog photography. I then trained

at the Iceland Academy of Arts, and was mostly interested in photography, and video-based

performance too. When I’m making and filming these more recent works, I’m looking

at film as a form of photography, inspired by these early days. Setting up the frames

for film is a similar process to assembling the composition of a photograph. Often

there is not much happening—I don’t play with the camera or use it hand held.

What is the starting point for your

works?

I usually begin with a limitation.

For example, the recent Krókótt / Crooked at the Reykjavik

Art Museum started from the question: how far can I ride my electric bike from a

certain location, and then back, and then pick up my girls’ from kindergarten, and

then home, without emptying the battery? The distance was about 40km. I picked a

random location on the map, rode the bike there, and back. While I’m riding on the

bicycle, I’m looking around, filming, stopping and listening, and recording my audio.

During this particular bike ride, I rode past this

wall—which is the main character in this installation. I thought—’okay, here is

another limitation!’ I repeatedly visited this site again and again and again with

a video camera and an audio recorder. From this limitation, something builds. From

that, I started writing. For a while, I felt like I was trying to pump life into

the wall by giving it a voice. That’s where it all starts from — limitations in

the landscape and an interaction.

What role does the narrator have

in your films?

For me, it starts with reading kids books for my children,

trying to understand the world as a child through a fictional fox, for example,

who is strangely speaking our human language.

Looking at this wall—this fortress—I cannot understand

it. That’s the first encounter that happens when I see these places. Usually, I’m

riding through the landscape, and everything looks ordinary, and suddenly there

are these shock moments of small things that capture my attention. I cannot comprehend

them, so I try to give them a voice in order to understand them. Then, within a

monologue that I write, I’m exploring my own thoughts on everyday life and how we

as humans operate within that environment. We speak to each other and converse.

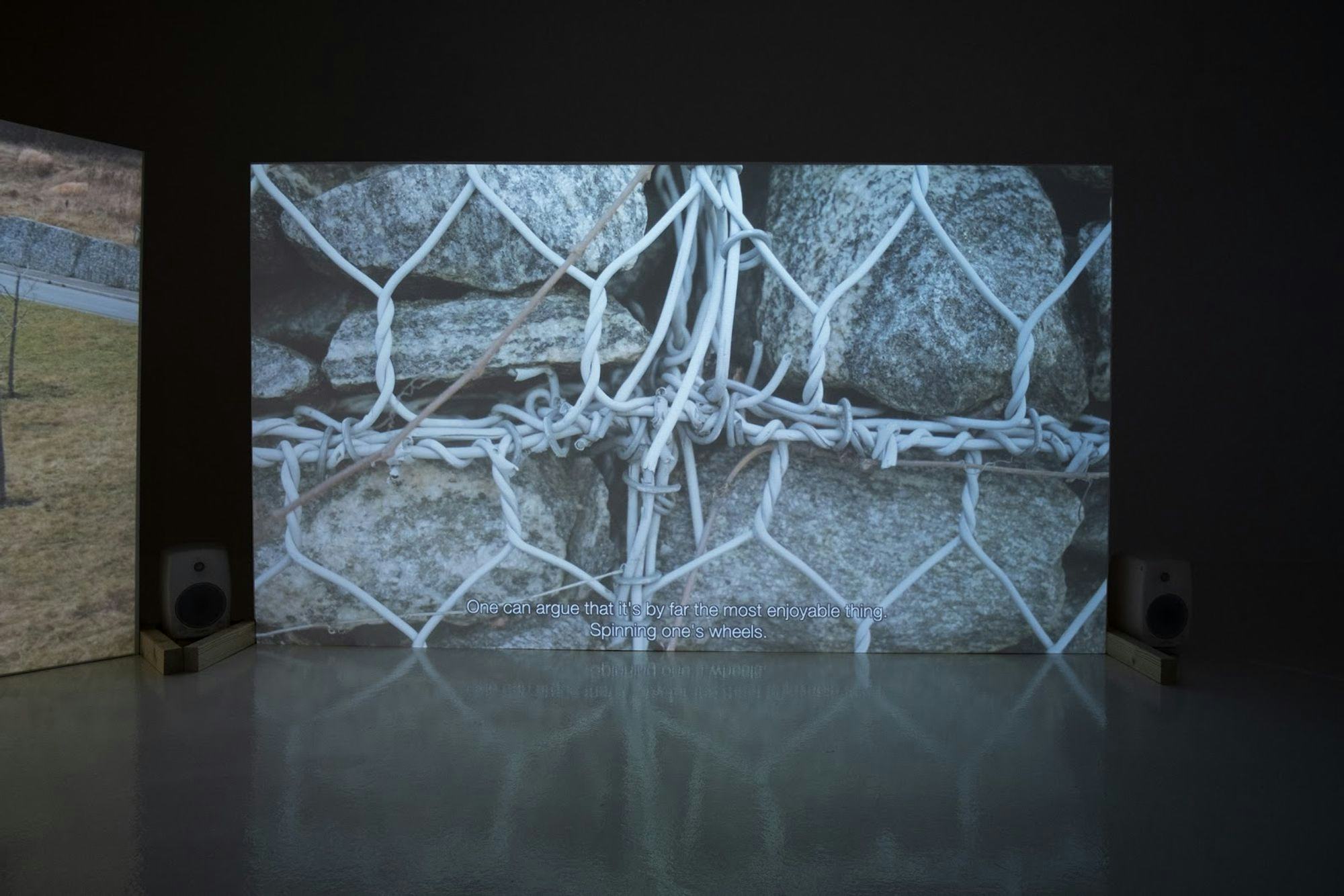

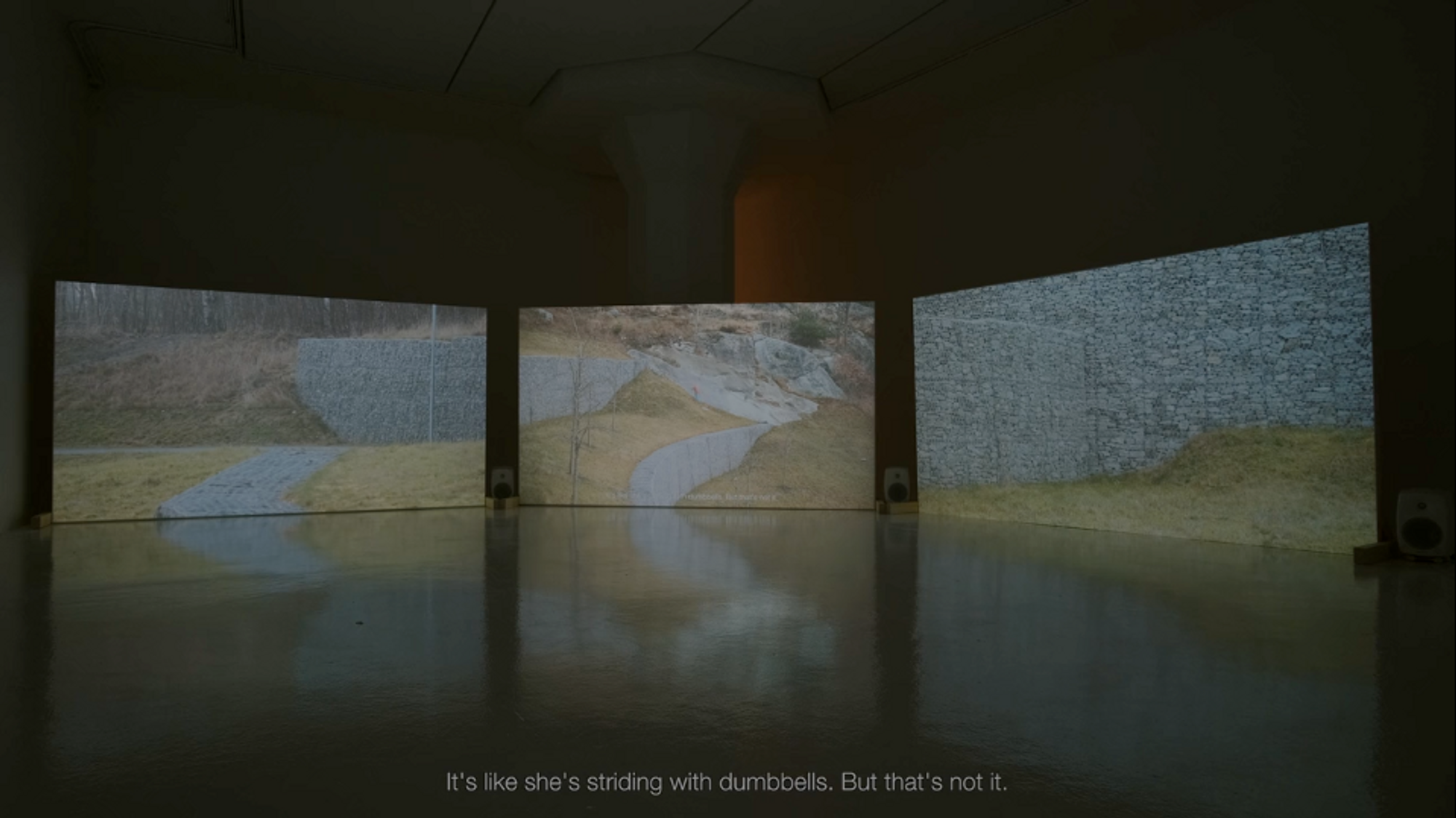

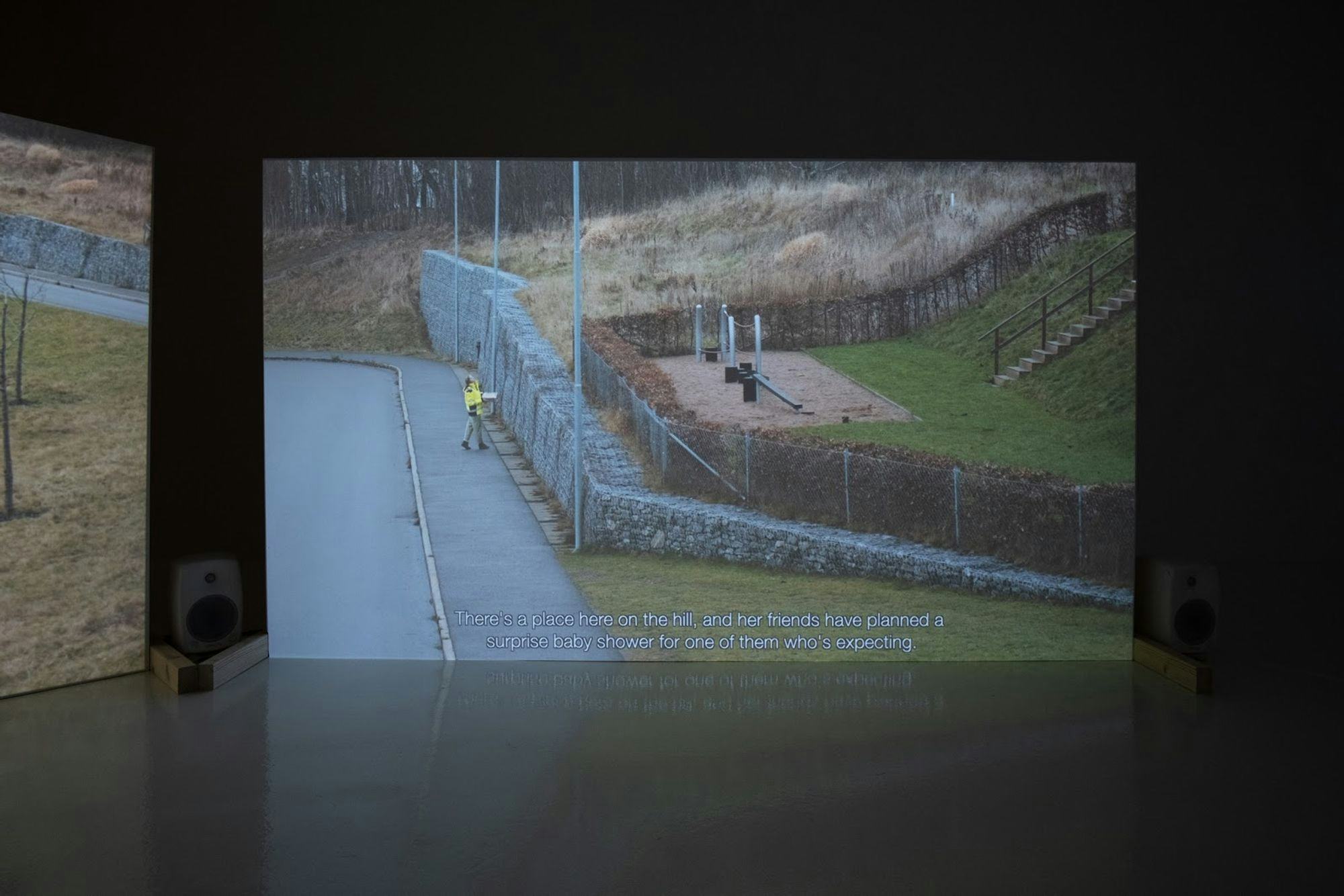

Klængur

Gunnarsson: ‘Krókótt / Crooked’, 2021. Now on view at the Reykjavik Art

Museum. Courtesy of the artist.

I see traces of Zoe Leonard or Icelandic

cinema in your work. Where do your inspirations come from?

In Drift, where you can

see the microphone, that visualisation indicates that it’s not just happening out

of nowhere—there’s an artist present, as someone who creates this. Agnes Varda has

inspired this thought process, as a director whose documentary work often can be

very experimental in narrational style, exploring where the voice comes from. Then

there is also Swedish director Roy Andersson, who has also been a big influence

on my work, with his grey, gloomy, Scandi, shitty, humorous tone, characters and

sets—their slowness and strangeness.

How important is the installation

and exhibition context for your films?

It’s a battle. For the last two years,

I’ve made work for installation at museums and galleries, but I’ve also produced

work for cinema and film festivals. It’s very hard to cross that line back and forth.

For instance, my recent installation at the museum, I find, doesn’t work well as

a single channel video, viewable on any handheld device. It’s the same with Drift,

which doesn’t work in a cinema environment. In that piece, I projected the subtitles

onto logs in the exhibition space, they’re an important part of that installation—it’s

not just an object projected onto incidentally.

Klængur

Gunnarsson: ‘Krókótt / Crooked’, 2021. Now on view at the Reykjavik Art

Museum. Courtesy of the artist.

Large, philosophical or earthly

questions about the man/nature binary and the anthropocene seem to whisper in the

background of your works. Do you agree?

The whole realm and craziness of the

anthropocene is too large to tackle in one installation. I’m very interested in

how, in our everyday activities we confront this problem of being within the landscape

and within the Nordic suburban city. We are constantly being sold nature—being urged

to ‘buy this place here, it’s very close to nature’. There’s always a friction that

occurs, which I’ve been looking at in Drift, Trinket

and the installation at Hafnarhús.

I’m also interested in the Reykjavik context. From

the Church Hallgrimskirkja, there used to be a clear view towards Esjan, the mountain.

Slowly through the last four to five years, it has been blocked. This January, I

noticed when I was home in the city that there are hotels being built that are blocking

the view. So we’re always stumbling onto something—we’re trying to reach nature,

but it’s obscured. We want to buy nature but we don’t want to really experience

or inhabit it—it exists as a facade for us.

I disagree with the way these anomalies

are being formed and sold. The fort and wall in Krókótt / Crooked is

sold to us with a sign that says ‘at one with nature’. But then, the first thing

you see is a wall that is not very inviting and is not at one with nature—it’s caged.

From that disagreement, I want to search for a common ground and a means of engaging

with the inanimate and the uninviting.

Klængur Gunnarsson: ‘Krókótt / Crooked’, 2021. Now on view at the Reykjavik Art Museum. Courtesy of the artist.

I wanted to ask you about politics

and aesthetics. Particularly through your work’s focus on walls, I can see traces

of Jacques Ranciere’s writing on Chantal Ackerman in The

Politics of Aesthetics. In that body of work, he remarks

that Ackerman’s depiction of the US-Mexico border wall treads the fine line between

its inherent politicisation, and yet its simple, formal beauty. Do you see the wall

in your films as having some sort of political dimension?

Yes, of course my work does. There is no escaping that.

There’s such a detailed decision and process behind designing and building such

a wall as the one featured in ‘Krókótt / Crooked’, it’s very long. I don’t know

how many people come to the table to agree on building the wall. That makes it a

political phenomenon, in the end—the decision to build a wall, by a lake, in a new

neighbourhood.

I don’t want to put critique in the

face of the viewer. The actor who read the texts in Crooked was asking me

how long it took to write, because it is not that long. I told him that it took

me many days to write it, because it is much more similar to poetry than a formal

script. I’ve always tried to figure out a line to walk on between the poetic and

political, because I’m very fond of an open experience of my work that can be taken

in different directions.

–

‘Crooked’

is on view at the D Gallery at the Reykjavik Art Museum until 14 March 2021.

-icelandic-pavilion-2000x2667.jpg&w=2048&q=80)