Your lockdown diary—a series of

drawings from each day during the pandemic—struck me as tragicomic and universally

relatable. Could you talk us through the series?

It was the middle of March when the

pandemic became serious in Europe, and I got into this really manic state. I just

started drawing, and posting them online for my friends. Their reactions pushed

me to continue. After a few of them, I had a lot of adrenaline to create more, and

I was fuelled by an anxiety about the uncertainty of this new virus. I decided after

a few posts to dedicate myself to become an independent news outlet during this

time. Everyday for a whole month, I was manically drawing from morning until night

time. The works are a graphic novel on the novel virus. I would like to eventually make a book out

of the project, and I’ve also printed them as physical works, which were on view

at Gallery Port. For me, their transition from being a purely digital project for

social media to becoming a physical entity is very interesting.

What is the relationship between

your drawings and performances? Is one medium more central to your practice?

I think the answer is both. It’s a privilege to develop

a concept in so many forms—and this exists more so in contemporary art, where there

are so few rules, and you can be many things at the same time. I really love that

element of being an artist. When you’re a young artist, or you’re working as an

artist for a few years, it’s very easy to slip off and get a day job, and then you

don’t have time or energy to do anything. So you have to have resilience, and be

stubborn, as an artist. For me, I’m not always in the mood to be performing and

talking to people, so when I feel like retreating into my introverted side, I start

drawing and making handicraft. I love mixing performance and drawing.

My new project for the Reykjavik Art Museum, as part

of the group show ‘Autumn Bulbs II’, is a mix of these mediums, because I will also

perform inside it. The piece is a bouldering wall, and it depicts zodiac constellations.

It’s inspired by my unborn daughter who is coming into the world next year. The

due date is in January, and she’s supposed to be an Aquarius, and if she’s early

she will be a Capricorn or a Capriquarius. I find these ancient symbols so fascinating—they

are really important for us to tell stories about each other and to understand each

other’s character. By making this work, I’m entering a huge rabbit hole of knowledge.

I used an app to create the composition for the wall—the ‘bouldering track’. I put

the app on the 23 January, and stood next to the wall. The signs are composed for

that specific date. It has a title, it’s Stjörnuliljur in Icelandic, in English

it’s ‘Astro Lilies’. I’ll give a reading of the zodiac, whilst climbing the stars.

I really look forward to seeing a human body in the painting—travelling around the

painting.

Styrmir Örn Guðmundsson

When you perform are you a character

or are you yourself?

More and more, in my performances I like to be myself.

I have occasionally worked with amateur theatre, but it’s also nice to embody the

position of a creator. It changes for me each time—it’s nice to challenge myself

to do new things. As an artist, I really don’t want to follow one formula for too

long.

Do you think your work is concerned

with the role of the artist, and what it means to assume this role in society?

Yes, I’m always investigating this role. There have

been times, where I truly believed that if everyone could be an artist, we could

have a very constructive world—but that might be problematic. Being an artist is

an important job in society, and those people who are titled ‘artists’, should be

those who are working at it everyday. It’s like with athletes—you might go to the

gym, but that doesn’t make you an athlete.

If there was another line of work

you were going to get into, what would it be?

I always wanted to be a scientist, before I went into

art. Even mathematics are fascinating. I’ve started playing instruments lately—and

that, for me, is a bridge between art and maths, or logic. Playing piano is poetic

and mathematical, direct and sensory. Real instruments like piano, or guitar, or

steel pan— are not art objects. But I’ve made some musical instruments myself that

are artworks. For instance, in my ‘Organ Orchestra’, there are different ceramic

organs, wind instruments, lungs, liver; the stomach is a percussive instrument,

the brain is a synthesizer. It’s a slow, ongoing work. I would love to record an

album with them.

Can you talk us through your album

that came out in 2018, ‘What Am I Doing With My Life?’

It started out without the whole ambition of a vinyl

album. On each stop of our DIY tour, I brewed and fermented a new version of the

performance, and new friends joined in. In the end, it was a full album, with some

15 guest artists.

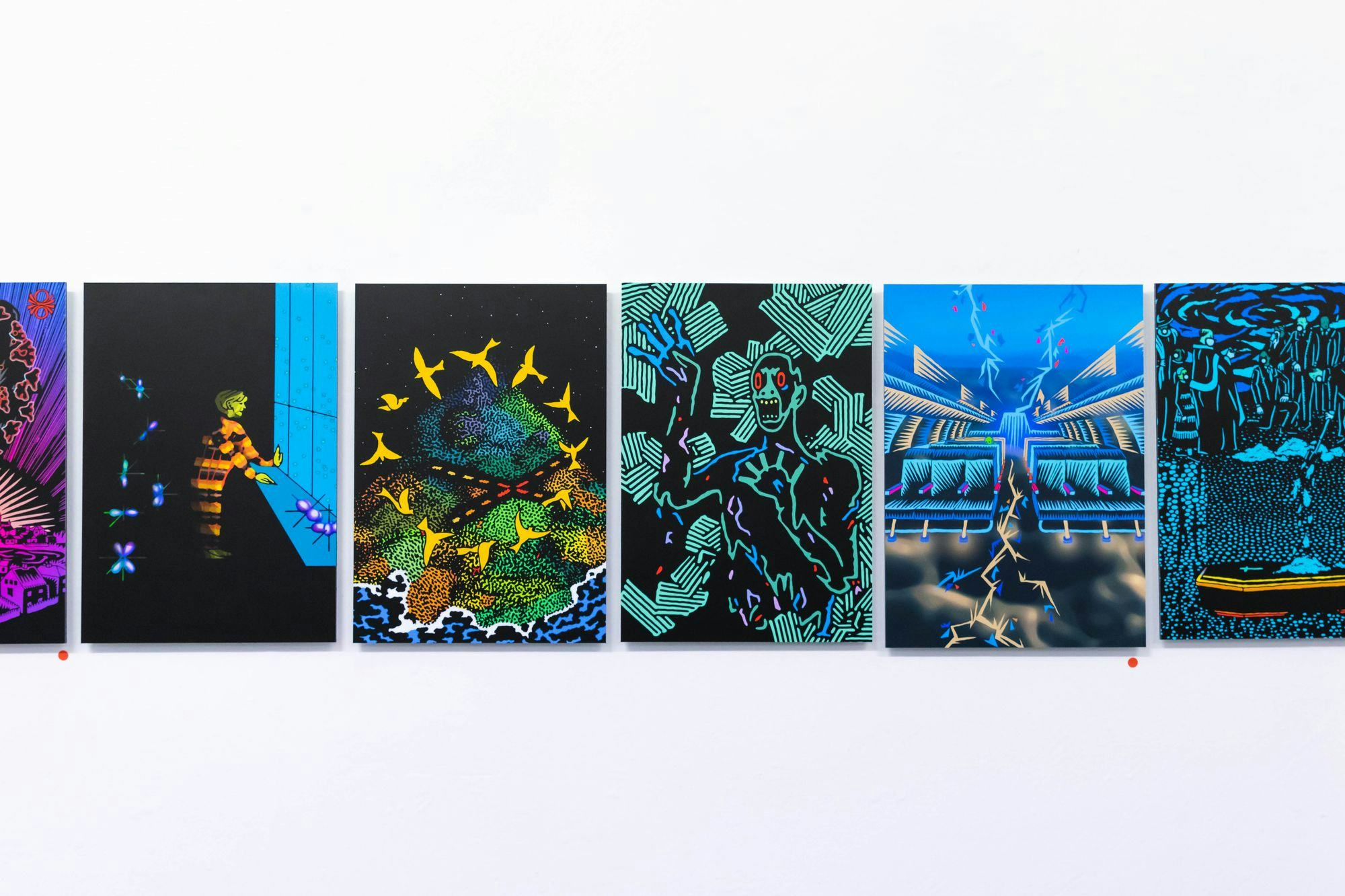

Styrmir Örn Guðmundsson. From the exhibition

Teikn á lofti at Gallery Port

Is collaboration integral to your

work?

Most of the time I’m on my own, but at that time I

felt a very big need to collaborate. It was a very extreme collaboration. It was

all driven by fun and humour and friendship, really. Friends who happened to be

artists and musicians.

Do you think that art should always

be humorous?

No, not at all. Art should be all of our emotions in

life. It should be political, it should be abstract and spiritual, and humorous

sometimes too. It should be really sad, thought-provoking, shocking or even terrorising.

I think the moment that art goes in only one direction, then it’s dead. Art should

be a mirror of humanity, and if we are all so different, and hold different behaviours

and beliefs—so art should reflect that.

Storytelling is the nucleus of many

of your performances. How important is literature, mythology or folklore to your

practice?

Narrative and storytelling is very much in my practice.

It’s deep rooted in our Icelandic culture. I have an instinct to tell stories from

childhood. As a young child, I played with toys and created imaginative stories.

Later in my youth, I began creating comics and stories before I knew anything about

art. It wasn’t until I was about 20 that I knew about any such thing as an ‘art

world’. I learned that everyone is invited to participate in art—everyone can make

and create. It’s the job of us artists to invite people who are not full time artists,

whether it’s children or older people, to teach and to try to open people’s minds.

Styrmir Örn Guðmundsson: Astro Lilies, 2020.

Styrmir Örn Guðmundsson. Performance, Astro Lilies, 2020.

How do you feel about your work

being presented online due to the limitations faced during the pandemic? Is there

something lost or gained when our idea of an art ‘public’ is reoriented?

There are some Icelandic artists who specialise in

online projects and digital art, namely the art collective ‘Hard-Core’—they were

[making digital art] long before Covid, they were doing everything that we are doing

now. During the pandemic, I got involved with a group of Icelandic artists to produce

digitally communicated art. We came together as a group in the confinement of COVID-19,

and we decided to make a day of performances, streaming online from Berlin, Hannover,

Helsinki and Reykjavik. For the first time, we decided to perform through a live

webcam, and made an event called Sunday Seven. It was 07/07, 7th July—it was very

experimental. We’re doing it again on the 10th of October, 10/10. So, maybe we will

have learned something from this virtual performance show. I think it’s cool that

people are adapting to our circumstances, it’s not a negative.

For instance, at Gallery Port, I came to Iceland to

bring artworks with me, but I had to go into quarantine. It was really funny, Gallery

Port put up an iPad with me on a call during the exhibition opening, and it became

like a performance. Some people were really chatty with me, but there were others

who were really creeped out.

One word I often see associated

with your practice is ‘absurd’. How do you feel about this interpretation? Where

did your interest in absurdity come from?

Sometimes I write the word, sometimes others have written

this word about me. I embrace this word as a form of play, especially when I tell

a story or when I work physically with material.

On the other hand, absurdity can be very negative.

I feel like Donald Trump is absurd and there is a sense of danger and of twisted

morality in its etymology. It shouldn’t be taken too lightly. Dada artists were

using absurdity as a means of responding to their political situation, which is

similar to our time now. Absurdity starts to grow in these precarious contexts as

an anxious reaction to reality. The fun side of it, used mostly by surrealists,

is where the absurd can be a kind of play. Making games, new rules or constrictions,

might lead to wonderful creations.

Styrmir Örn Guðmundsson. What am I doing with my life? – Performance – 30 min – Autarkia, Vilnius – 2017.

Styrmir Örn Guðmundssonis currently artist-in-residence

at Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin, where he will have an upcoming exhibition.

The group show ‘Autumn Bulbs II’ at Reykjavik Art Museum runs from 24 September

– 18 October 2020.

-icelandic-pavilion-2000x2667.jpg&w=2048&q=80)