La Biennale Captures the Current Zeitgeist for Indigenous Voices to be Heard, but Are We Really Listening?

If there ever was a perfect time for Indigenous voices to be heard at the Venice Biennale, it would be now. That is, given that the curatorial concept is anchored in Post-humanism. Relevantly reflected in the amount of Indigenous artists presenting this year. It should, however, be considered what it means for Indigenous artists to enter the „stage“ of the Biennale given its dark and unjust history towards Indigenous people.

History

Not too long ago the common consensus in academia and western discourse was that Indigenous cultures were less developed than in western society. They were considered primitive in nature and their way of life was without much relevance outside its own cultures. Furthermore, their creative endeavours were rarely, if ever, considered art but rather to be craft – or ethnographic material. However, in the latter half of the last century Eurocentric attitudes started to change.

Largely due to changes in anthropological research and a shift in attitudes towards Indigenous knowledge systems, following the devastation of WWII – there was a rise in the inclusion of the perspectives of Indigenous individuals themselves in these fields of research. Consequently, two important facts were revealed; on the one hand that Indigenous groups had worldviews and traditions that were relevant to their environment as well as reaping benefits and more holistic approaches outside of their own cultures. And therefore not to be seen as “less developed”. On the other hand, that some Indigenous cultures did not have a term for art that mirrored western views and therefore its value shouldn’t be upheld to western aesthetic standards.

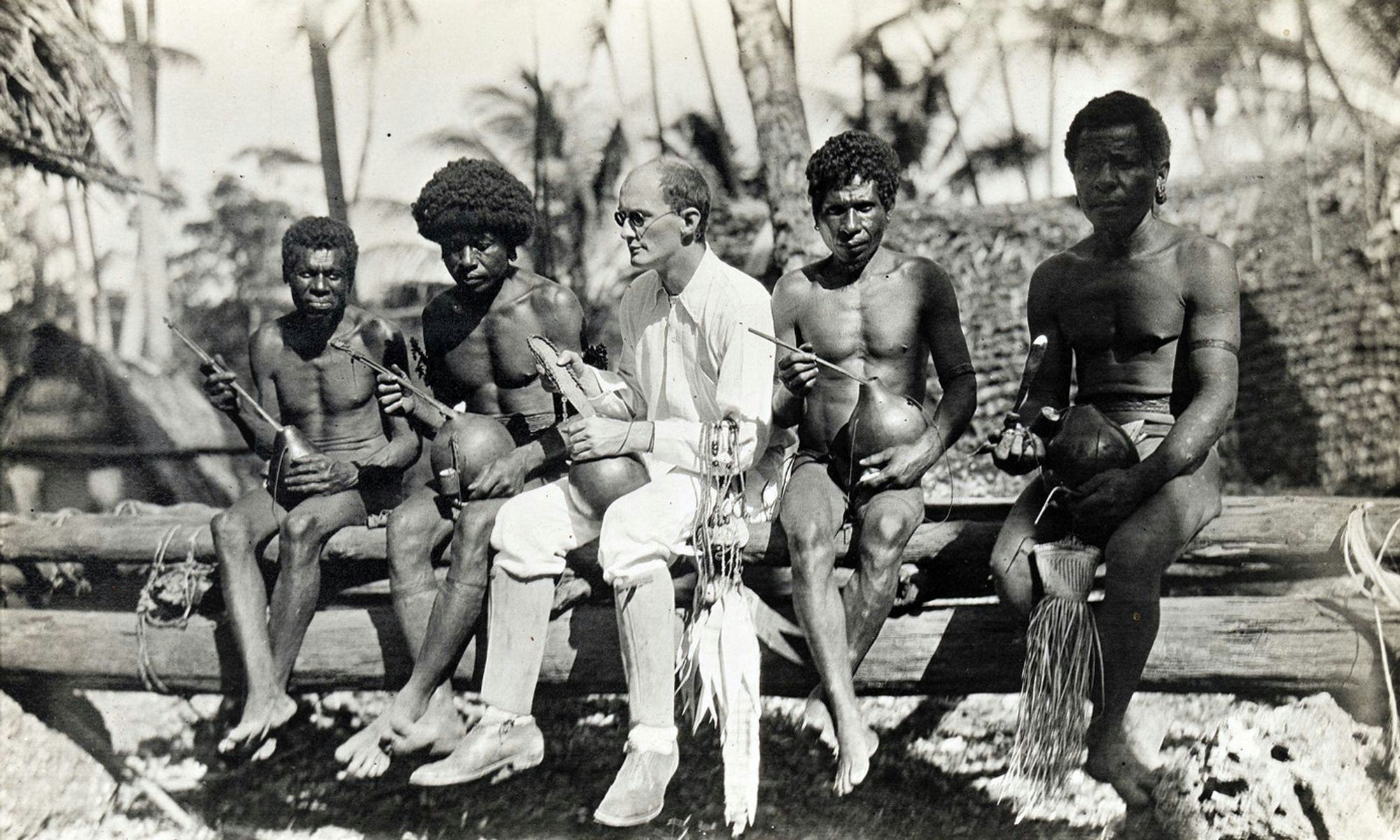

Bronisław Malinowski anthropologist with the Indigenous people of the Trobriand Islands. Photographed in 1918.

This supported the need for reconsidering how art was defined, for example to include “craft”, as well as departing from the belief of a Eurocentric linear progression of societies throughout history. Which ultimately created space in western discourse for marginalised people; voices outside of western central discourses, to be heard. A factor that has certainly had an affect on the growing notoriety of Indigenous culture and art in recent years – both in popular discourse and in the contemporary art world. This eventually lead to the growing veneration of Indigenous culture and artists in recent years – both in popular discourse and in the contemporary art world.

Indigenous voices become heard: La Biennale di Venezia

For more than three decades, Indigenous artists have sporadically been presented at La Biennale di Venezia. In 1990, in the exhibition titled Future dimensions, The Aboriginal Arts Board of the Australian Council nominated, Rover Thomas and Trevor Nickolls, to represent Australia who were the first Indigenous artists to participate. Edward Poitras was the first to represent Canada in 1995, the curatorial concept then being Identity and Alterity, and Tracy Morphatt was the first solo artist to represent Australia in 2017, under the Biennale main exhibition titled Think with the Senses – Feel with the Mind.

More recently, the Canadian pavilion was represented by Nunavut‘s Isuama Collective in 2019, main exhibition being May you live in interesting times; New Zealand was represented by Maori artist Losa Reihana in 2017, in La Biennales edition titled Viva Arte Viva – inspired by humanism and this year, the New Zealand national participation is represented by Sāmoan-Japanese artist Yuki Kihara, coinciding with the Il Latte Dei Sogni exhibition.

Although many Indigenous groups and individuals have been present at the Biennale for the last decades – the curatorial vision for this year’s Biennale might be one that is most appropriate and relevant in supporting Indigenous voices. Moreover, given the zeitgeist of our time. Like Josie Thaddeus-Johns expressed in her article for Elephant regarding the presence of Indigenous people in this year’s Biennale:

„In the Biennale pavilions, Indigenous attitudes to nature represent a holistic, sustainable alternative to the extractive capitalism that colonialism wrought. They seem especially relevant in a time of global climate crisis. “

Josie Thaddeus-Johns

The Indigenous people and knowledge systems are historically marginalised along with their unique longstanding holistic relationship with nature being historically underrated. Thus they represent a paragon of a way of life that seems perfectly fitting to fulfil desires of post-humanist ideology. It is no wonder then why so many Indigenous artists are represented in this year’s biennale which grounds its theory in post-humanism.

The large amount of Indigenous artists presented is a positive development for La Biennale di Venezia and ought to be celebrated, it should however, be thoroughly considered what it means for Indigenous artists and cultural practitioners to enter the „stage“ of the 59th international art exhibition.

-2017-2000x1334.jpg&w=2048&q=80)

Ernesto Neto, Un Sagrado Lugar (A Sacred Place), 2017. Image depicts the installation activated with the Huni Kuin, or Kaxinawá, Indigenous people living in the Brazilian state of Acre, and in Peru, the Amazonian forest.

The relationship between the venice biennial and indigenous people

Indigenous people are often under the aegis of countries that have historically colonised and oppressed them. The artistic positions of the Indigenous therefore have different meanings in the national pavilions

The Biennale was founded on the ‚world‘s fair model‘ a.k.a. Exposition Internationale. Which can be defined as having the function of “bringing culture, history, and new technology together in one event to people of many backgrounds” or as being “a large international exhibition to showcase the achievements of nations”.

As Candice Hopkins, a curator of Tlingit Indigenous descent who worked on the 2019 Canadian pavilion pointed out „[the Venice Biennale] has a dark history associated with it, particularly with/in regards to native people being on display.“ One has only to go back 5 years to find such a display of Indigenous people – with the work of Ernesto Neto curated by Christine Marcel; Sagrado Lugar (A sacred place) in the Brazilian pavilion. Therefore the visibility of Indigenous cultures at the Venice Biennale is not always equal to appreciation to Indigenous culture or redemption for its people, when the artists themselves aren’t of Indigenous descent themselves.

Considering this, as well as the popular growing interest in Indigenous culture, it is not only appropriate but necessary that Indigenous people themselves are the ones to mediate their own culture on their own terms. What is to be determined is whether they are able to do so in a way that elevates or honours their heritage, identity and culture in visual art settings such as the biennale-format which originates from the very world system that marginalised Indigenous people in the first place.

Indigenous art at the Venice Biennale 2022

Reoccurring themes which are to be found in national participations presented by Indigenous artists are colonialism, tradition and motifs that relate to nature.Given the theme of Post-humanism along with the context of the Biennale ‘s history and the broader history of oppression and the marginalisation of Indigenous people, the prominent focus on colonialism seems only appropriate. The presentation of cultural symbolism seems to be more apparent in artworks that are represented by Indigenous artists. Almost every artwork in this year’s Biennale that is presented by these communities is characterised by the traditional motifs – while western settler countries are not (e.g.ex. France, Canada, England). In this regard, it could therefore be assumed that using traditional symbolism is very important for Indigenous artists and is the foundation of their contemporary identity, whilst it is not as strong of an incentive of non-Indigenous and non-marginalised artists. However, the fact that Indigenous artists rely on the traditions of their communities in their creative outputs – does that in actuality help predominantly western and white audiences relate to Indigenous culture or does it strengthen a sort of an otherness about Indigenous people? In other words perpetuating an „us“ and „them“ dynamic? Similar to older iterations of the International Exhibitions.

This needs to be kept in mind whilst regarding and contemplating the Indigenous artwork at this year’s la Biennale di Venezia.

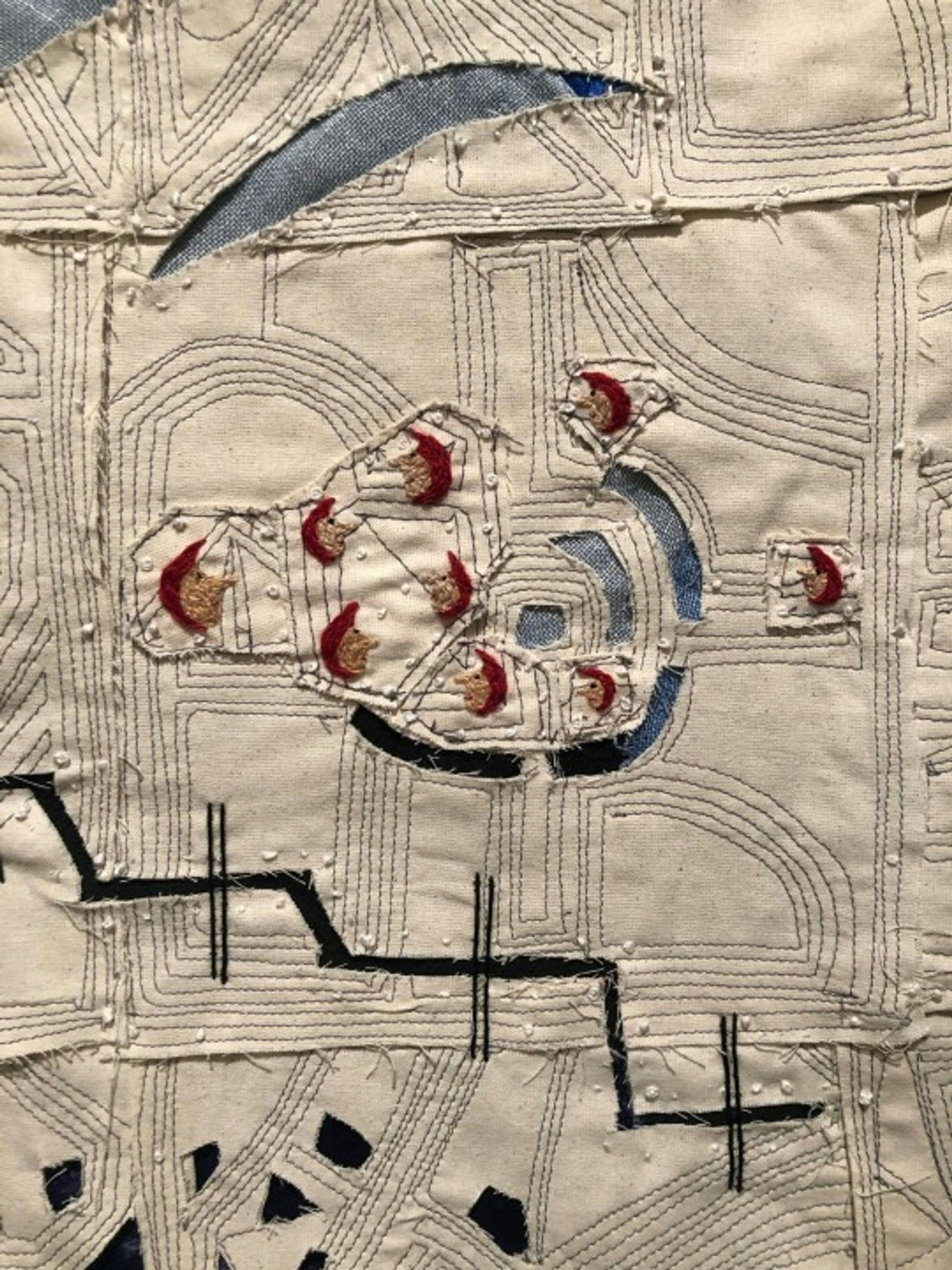

Britta Marakatt-Labba, In the footsteps of the stars, 2021.

Sámi storytelling in il latte dei sogni

One of the first artworks in the curated exhibition of the Arsenale, Il Latte dei Sogni curated by Cecilia Alemani, is by the Sámi artist, Britta Marakatt-Labba. She was born into a family of reindeer herders in Sápmi, home to the Sámi community. Her work consists of embroidery work that at first glance resembles something that would be traditional Sámi or Nordic embroidery, however, she has developed her own unique embroidery method in her artistic approach. Framed on one of the walls in Arsenale, they depict a mode of storytelling of the Sámi people in the Nordic landscape.

The stories she is telling are foreign to me, yet somehow relatable. The modest aura of her work is inspiring and invokes an appreciation for softness and an “ordinary”, slow-paced life. Her artwork very much stands out amidst the very grand pieces that surround her delicate pieces in the Arsenale. A factor that surely plays into the emotional effects of her work. In my opinion, the work of Marakatt-Labba deepens the respect for Indigenous culture and strengthens a sense of solidarity. She is able to portray her art free from political agenda and yet it stands tall and speaks volumes to socio-political realities of Indigenous cultures in the global landscape.

Gerardo Tan, Felicidad A. Prudente, and Sammy N. Buhle, Andi taku e sana, Amung taku di sana / All of us present, This is our gathering, 2022.

The Philippine pavilion

The group of artists representing the Philippine Pavilion can not exactly be described as Indigenous, not collectively at least. However, they share unique insight and extensive knowledge of Filipino culture and traditions which can be discerned from their installation, All of us Present, This is Our Gathering. Felicidad A. Prudente is for example is for example one of the leading ethnomusicologists in the Philippines and Geraldo Tan is a contemporary artist who has represented the Philippines in various international art exhibitions. Whilst Sammy N. Buhle comes from a family of weavers who taught him the craft at an early age; he belongs to the younger generation of weaving artisans in the Ifugao Province. Hence, making him the person of the group with the most intimate connection with Filipino Indigenous traditions. Nonetheless, Buhle usually participates in trade fairs and similar events, making the Venice Biennale Buhle’s first official art exhibition participation – a factor that is relevant to take into account while processing the Philippine contribution.

Entering the Philippine pavilion, one does so through a hallway created with a wooden pallet that conceals the rest of the room. In the hallway there are large video projections of Indigenous people singing or performing some kind of vocalisation. The videos show close-ups of a mouth of the man who is vocalising something. The sounds from the video echo in the large space where the Philippine exhibition continues. In it are long materials of textiles spread on the floor with smaller video screens at the end of them that show the process of the weaving. The weaving patterns resemble seemingly familiar symbols that have typically been associated with Indigenous identities in popular media throughout the years. It is a tribute to Filipino Indigenous culture, as the curatorial text of the exhibition states:

„the exhibit aims to represent the translation of cultural data into visual communication, collectively promoting Philippine traditions and ensuring its endurance through universal exchange.“

Gerardo Tan, Felicidad A. Prudente, and Sammy N. Buhle, Andi taku e sana, Amung taku di sana / All of us present, This is our gathering, 2022.

While aiming to ensure the endurance of tradition, the artists do so using very traditional and perhaps stereotypical motifs. Moreover, there seems to be a missing element that gives it deeper meaning – in order to distinguish it as art and separate it from being mere artefact or data preservation. Secondly, to give the audience something else to relate to other than stereotypical ideas of Indigenous communities.

Although, this critique may remind you of the old attitudes towards Indigenous art covered here above – measuring it more for its ethnographic value rather than artistic value. Therefore possibly revealing a perception which might be inherent in western value discernment of something foreign, as well as revealing my own privileged biases and social position?

The background of one of the artists is worth noting in this context. Geraldo Tan works with a variety of media and deal with issues of representation and conceptual plays. He often appropriates reproduced images from the world of art and from mass-media using a variety of media in order to subvert hierarchies and give way to new itinerant meanings.

Given that this is the approach of Tan’s works, the use of traditional symbolism makes perfect sense. However, the itinerant meaning of these traditional Philippine symbols, in the Biennale, do not clearly subvert western hierarchies. If it was in fact the intention of the work, for the audience to come to the conclusion of discovering their own prejudice, then it might be a rather far fetched attempt. Firstly, because most audiences probably do not know the background of the artist(s). Secondly, the audience in attendance at the Biennale more often than not come to see as many pavilions as they can, therefore they cannot ideally contemplate deeply on all of the artworks they encounter. Therefore, using traditional symbolism as some form of satire would be very risky in this context. Given the weight of presenting Indigenous culture at the Biennale, it would seem relevant for artists, and curators, to try to distance their work from traditional ideas. However, if they choose to use those kind of symbols, then it has to be of great and obvious relevance to give some additional context to them.

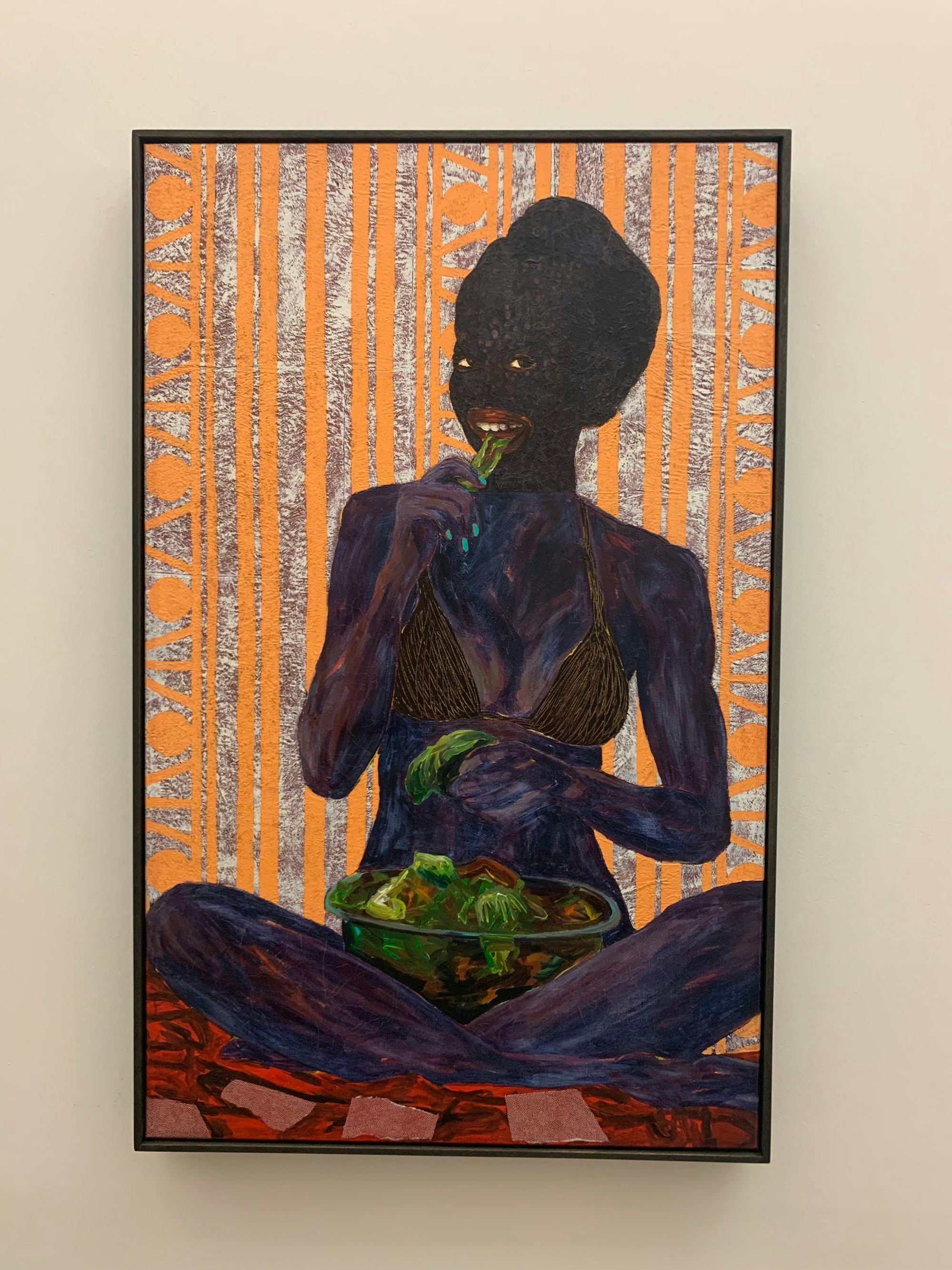

Collin Sekajugo, Radiance: They dream In Time, 2022

A good example of this done effectively is the artwork in the Uganda pavilion.The artists of the Uganda pavilion use traditional symbolism as a very obvious form of satire. Which ultimately relates to a more powerful position of the artists. They claim authority over these symbols by altering them for the presumably desired effects of evaluation of a stereotype. In the case of the Uganda pavilion then, the context given with the obvious satire, lends itself more to be evaluated in favour of the culture presented.

Anders Sunna, ‘Illegal Spirits of Sápmi’, 2022.

The Sámi pavilion

This year, the conversion of the Norwegian, Swedish and Finnish into the Sámi pavilion for this Biennale edition, represents a historical first at the Biennale. When entering into the Sámi pavilion guests are confronted with large paintings, triptych, that depict the relationship of the Indigenous with the „white man“. Recalling the legacieso of colonialism and the destruction and pillaging of the land of the Indigenous. The paintings are painted on large wooden pallets that are placed in a row, the “last one” being made to look like as if it had been burned and vandalised.

Anders Sunna, ‘Illegal Spirits of Sápmi’, 2022.

Another part of the pavilion contains sculptures that are made from traditional material, although material which surely is not traditionally used for decoration. These materials are organs from animals.

The final part of the pavilion is a documentary depicted on two screens of which each forms a tent setting behind them. The documentary furthers the theme of colonialism and connects it with the destruction of natural habitat in the northern regions of the Sámi people. In front of the screens are seats for guests that are made from tree stubs.

In my opinion, the artists are really playing well with the tension between getting a message across whilst partaking in an event, that has historically excluded mainly being available to their oppressors. The piece is highly political but it is only fitting in light of the Nordic Pavilion being dedicated to Sámi communities – not to mention the curatorial concept of the main exhibition and the relationship of the Biennale and indigenous people this year.

It is clear that the presentation of Sámi artists bears great significance to the global discourse that exceeds solely being recognized by the artworld. A point that Ándé Somby‘s elaborated on:

“Indigenous rights can be summed up as the right to one’s past, present, and future. [..] These rights are often violated, and for the three artists in the Sámi Pavilion, art has become the last resort after political and legal action has failed.“

The Sámi pavilion exhibition is not only a criticism of colonialism but a fight for a community’s identity and rights. That is, rights that are established with a recognition of their history and culture on their own terms. What is interesting is that in order to do so it seems necessary to do it by presenting a part of their history that involves their oppressors. Even though it is surely not a main point in how Indigenous culture should be defined. The history and culture of Indigenous people involves so much more but all of that cannot be overshadowed by a predominant western narrative. That is something to keep in mind while visiting the Biennale.

I would like to end this article with a statement of Wanda Nanibush, the founder of aabaakwad, an annual gathering by and with Indigenous artists and cultural workers.

“We are more desired at certain moments in history than others, usually following large protest movements. Movements around the world against mining and climate change—that’s when people start looking again to Indigenous folks, including artists, for avenues, alternatives, ways of going forward.”

Wanda Nanibush

With that being said, it is important that the veneration and appreciation of Indigenous people and culture in this year’s Biennale does not only signify a trend of the moment, that will then fade out. One way to make sure that these conversations will have a platform consistently would be to make the Nordic Pavilion the Sámi one permanently.

-icelandic-pavilion-2000x2667.jpg&w=2048&q=80)