As I walked through the exhibitions and pavilions at the 59th edition of the international art exhibition in Venice, I noticed a strong theme decisively reflecting what is happening outside the “art world”. One of the most noticeable topics addressed, as Cecilia Alemani presents in her statement, is the de-centring of the western idea of the “human”, and celebrating other perspectives in its place[1]. This theme pervades the biennale: and can be found in many of the pavilions as well as in the central exhibition curated by Alemani.

The formal exhibitions at La Biennale di Venezia are split into two categories (three if the collateral events are counted as well). On the one hand, there is a vast curated exhibition at the two main sites, Giardini and Arsenale. On the other, there are the national pavilions where the nations participating exhibit their contribution, also situated in Giardini, Arsenale (where the Icelandic Pavilion is located), and all-around Venice.

This year, the curated exhibition bears the title The Milk of Dreams. Alemani invites the visitors on a journey to reimagine the transformations of bodies and their possible combinations. In the exhibition, she emphasises the connection between humanity and nature, societies and cultures, and associations between bodies and technology. Posthumanism is prevalent throughout the exhibition; a school of thought criticises the centrality of the “human” in the natural world and de-stabilises the various humanistic dualisms such as the man/nature divide and the dualism between self/other[2]. In concordance with this exhibition theme, many artists reflect on the de-centralisation of the white western male, and the exhibition dispenses with the idea that he is a universal criterion for “humanity” in itself[3]. For example, most artists in the exhibition identify as female or non-binary and come from 58 different countries. Diversity is, nevertheless, not an official goal of the exhibition; instead, it is a result of the theme that Alemani presents.

Simone Leigh, Brick House, 2019.

The first space one visits in Arsenale is a perfect example of the de-centralisation I discussed. The huge, almost three-tonne sculpture, Brick House (2019) by Simone Leigh sets the tone. The hollow bottom of the sculpture imitates a construction, or a kind of house, while the top part is a bust of a young black woman with a gentle Mona Lisaesque smile. The bust is simultaneously majestic and a bit eerie; maybe the lack of eyes stimulates an uneasiness within me, but most of Leigh’s works are without faces[4]. It could, therefore, be the striking style of the artist at work, but I felt in the room as if there was more to the eyelessness than meets the eye.

It was as if the sculpture described how it is to not have a valid perspective. The “house” part of the sculpture draws inspiration from, among other things, a restaurant called Mammy’s Cupboard, which is situated by a freeway in Mississippi. For Leigh, Mammy metaphorically represents how the work and role of the black woman are equal to her body[5]. The de-centralisation that threads the whole exhibition consists, in this work, in re-evaluating the history and the role of the black woman in US society through the sculpture.

Many national pavilions of the European and the English-speaking world at the 2022 biennale participate in a similar strand of introspection about the actual social structures of the nations they represent—thereby de-centralising the Western humanist perspective. These pavilions emphasise the voices of indigenous people, and postcolonialism, and exhibit works from minorities often underrepresented within the art world. Simone Leigh is also the representative for the US national pavilion, where she calls attention to the subjective viewpoint of the black woman in her unique style[6]. But the topic is on the mind of more nations than just the US. For instance, the representative for New Zealand, Yuki Kihara, shines the spotlight on her social group, the third gender of Samóa: Fa’afafine, with caricatures of Gauguin paintings—addressing the western gender binary[7]. Małgorzata Mirga-Tas takes inspiration from her roots, but the installation in the Polish pavilion shows twelve months of the year in the patchwork style of Roma[8]. In the French pavilion, Zineb Sedira investigates militant films against colonialism in Algeria[9]. Lastly, the winner of the golden lion for a national pavilion, Sonia Boyce, explores the vulnerability inherent in cooperation through the improvisation of British black female singers[10]. Each of these pavilions truly deserves to be closely discussed and analysed, but it would be overly ambitious to discuss all of them in this one article. Therefore, from here on, I will limit my discussion to our neighbours here in the north: the Sami because they are, for the first time, well-represented at this year’s biennale.

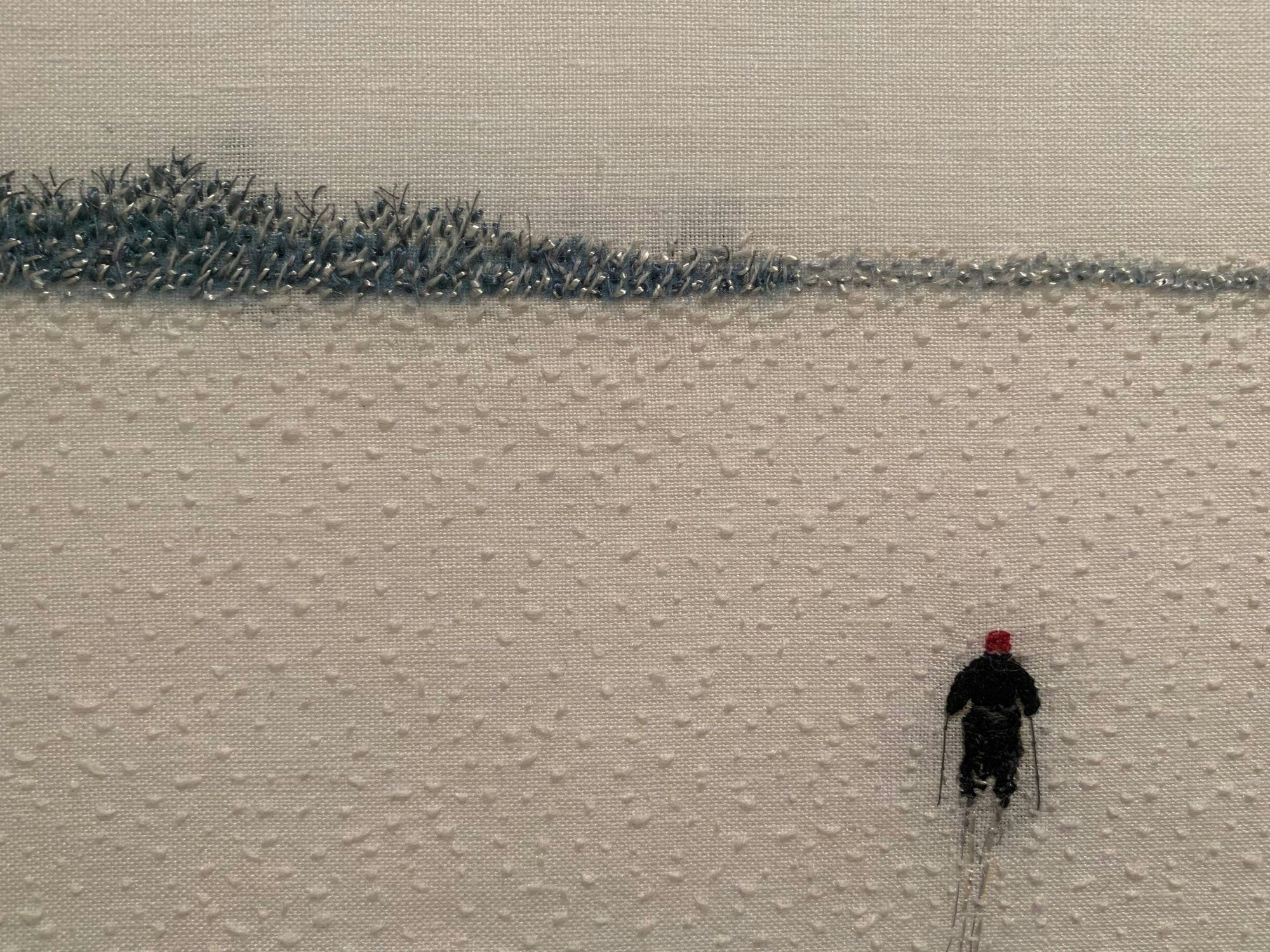

The knowledge and worldview of indigenous people play a significant role in The Milk of Dreams. Therefore, the first spaces at the Arsenale emphasise these worldviews and spiritual cultures from all over the globe. The embroidered works of Sámi artist Britta Marakat-Labba are positioned in this context and beautifully exemplify the magic in the environment. I was immediately captured by the small-scale embroidered works the first time I saw them at Arsenale. Some portray little globes encapsulating snow-covered winter wonderlands framed by flora, fauna, people in sleeping bags and little women with ladjogáhpir, a traditional Sámi hat[11]. Other works are small-scale embroidered landscapes sown on white material, where the intentional gaps between the stitches portray the snow in the landscapes. This technique creates a snowfield that communicates a feeling of peacefulness and tranquillity that is yet full of life.

Britta Marakat-Labba, One Day in November, 2021

Something about the snow-covered landscape moved me, and the night we know so well here in Iceland, portrayed in Marakatt-Labba’s embroidery, becomes magical. The surrealist elements of the embroidery are mixed with the reality of the Sámi people. The methods of Sámi visual storytelling, with its magical nature, get space in Arsenale and underline the post-humanist de-centring of the western perspective towards nature.

As beautiful as I think the works are, (they are my favourite in the exhibition); I still feel a mild melancholy as I view them and ponder. I was raised in the Nordic countries, Denmark and Iceland, and most of us here in Iceland think of ourselves as the next-door neighbours to Norwegians. Nevertheless, my knowledge of Sámis was extremely shallow. I don’t believe that I’m the only one here in Iceland that practised a certain inattentiveness about the position of the Sámi within Nordic society and their cultural heritage. The closeness fosters the unsettling feeling about how harmful the homogenous image of the Nordic countries is; I should have known better. The hype and adulation surrounding the Nordic Vikings distort the image of the nations, internally as well as externally, by casting a shadow on the present diversity and the problems that this social group faces.

This year the Nordic Pavilion (Sweden, Norway and Finland) faces this harmful image. The transformation of the pavilion into the Sámi pavilion has symbolic value in acknowledging the sovereignty of the Sámi people, and this is the first time that they are the representatives in the Nordic pavilion at the biennale. The Sámi live across the Nordic borders and have done so before the borders were mapped. It is a diverse culture with multiple social groups that speak over ten languages. There are works by three artists in the pavilion: Pauliina Feodoroff, Máret Ánne Sara, and Anders Sunna. I specifically liked the works by Máret Ánne Sara, and I stood there wide-eyed, looking at the dried reindeer and reindeer skins that she had hung up with threads. The work Ale suova sielu sáiget (2022) reminds me of a windchime. The hanging sculpture rotates slowly and consists of dried calves and plants. A specific smell accompanies the work, a type of outdoor smell.

Foreground: Máret Ánne Sara, Gutted – Gávogálši, 2022. Background: Máret Ánne Sara, Ale suova sielu sáiget, 2022. Photo: Michael Miller/OCA

Sara gives the work the symbolic meaning of being anxious for a future where the livelihood of the calves is at stake, and the future of the Sámi people is endangered as well[12]. In essence and materially, the works are not made to last forever: they are neither made from plastic nor porcelain. I found that fact added something genuine to the work—making it appealing, beautiful, and symbolic. The organic character of the works reflects well the bodily portrayals of emotion that she expresses in the works.

The political atmosphere of the Sámi pavilion is direct. One can read Sámi values alongside the works, and the works address the political reality of the Sámi and their history. For example, the artworks of Anders Sunna address the policies that contradict the rights of Sámi peoples in Sweden and juxtapose colonial legal documents with visual storytelling. A conference was also held by aabaakwad and the Sámi pavilion at the biennale’s opening where a panel confronted big questions about nationhood, the position of indigenous groups within the art world and the political status of indigenous groups against colonialism. The conference is all online and, on the website, it is possible to listen to all the discussions[13].

Anders Sunna, Illegal Spirits of the Sápmi, 2022. Photo: Michael Miller/OCA

By giving the Sámi the pavilion space, a revision of the national identities takes place that now accepts the part of Sámi within their own identity. The de-centralisation of the homogeneous Nordic countries and the colonising strategies they have adopted toward the Sámi people are underlined and criticised severely. It is, however, difficult to say how far such a revision goes: whether it has real effects on legislation and will result in a better livelihood and more respect for Sámi culture or whether it is only present within cultural institutions. I do want to hope that artworks mirror the zeitgeist, a sort of a focal point of what is to come and a way to express what has not yet been established within the bureaucratic world of legislation and policy.

A similar question can be posed about the possibility of art to criticise colonialism and appreciate diversity within a structure such as the Venice biennale. The biennale is the oldest, still running, biennale and has been operative since 1895. However, the national pavilion structure is a bit outdated and has been criticised as a contemporary “colonial exposition”. For example, Simone Leigh transformed the US pavilion into a tribal building akin to what was exhibited at the colonial exposition in Paris in 1931, and she named the work Façade (2022). Moreover, the Venice biennale is often compared to the Olympics of the visual art world, as the cultural minister of Iceland, Lilja Alfreðsdóttir, noted at the Icelandic pavilion’s opening. That kind of language encourages the idea of competition, national pride, nationalism, and all that follows when nations are pitted against each other. Nations exhibit specially chosen artists as representatives that are more often connected to the nation’s image. In that way, the national pavilion arrangement of the biennale encourages stereotypes, borders, and nationalism. An extra complication is therefore implicated when the art within the national pavilions challenges their social structure and colonialism within the framework that typically strengthens socially constructed borders. Irrespective of the shortcomings of the context of the Sámi pavilion at the biennale, there is still a whiff of hope in the air, and it might be possible to think of the national pavilions at the biennale and criticism of colonialism as not mutually exclusive.

Finally, it is interesting to feel and see all the attention and interest these pavilions get. They participate directly in the discussions outside the biennale or the art world, reflecting the trends of the now. Of course, it is impossible to tell what the future will hold regarding the rights and status of the social groups that get space at the biennale; however, one thing I’m sure of is that those snow-covered landscapes melted my heart.

Footnotes

[1] “Many contemporary artists are imagining

a posthuman condition that challenges the modern Western vision of the human being

− and especially the presumed universal ideal of the white, male “Man of Reason”

− as fixed centre of the universe and measure of all things.”

[2]https://oxfordre.com/communication/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228613-e-627

[3] https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2022/statement-cecilia-alemani

[4]https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/29/arts/design/simone-leigh-sculpture-high-line.html

[5] https://www.hauserwirth.com/ursula/28500-making-simone-leighs-brick-house/

[6] https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2022/united-states-america

[7] https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2022/new-zealand

[8] https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2022/poland

[9] https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2022/france

[10] https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2022/great-britain

[11] https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2022/milk-dreams/britta-marakatt-labba

[12] https://oca.no/thesamipavilion-maretannesara

[13] https://aabaakwad.com/current-gatherings/

-icelandic-pavilion-2000x2667.jpg&w=2048&q=80)