Ragnheiður Sigurðardóttir Bjarnarson and Snaebjorn Brynjarsson are the magic couple behind Midpunkt, a gallery in the basement of an old ice cream shop Ragnheiður’s family ran in Kópavogur when she was a child. Championing inclusivity through open calls and all kinds of experimental and immersive practices, the gallery aims to do things differently—to date, they have had more shows and performances than you can count. There is a lot of method and care that has gone into the consideration of the space, and Ragnheiður tells the oral history of the gallery’s inception in her conversation with us below.

You’re doing an open call model, could you talk a bit about why you chose that as a strategy for selecting artists?

We like the concept of an open call for a few reasons. Me and my husband started Midpunkt after we moved back to Iceland from living abroad in Brussels and Paris. I changed profession—I left Iceland as a dancer and a choreographer, and I came back as an artist. I’d always been part of the contemporary art scene as a dancer, and also through performances, but I didn’t study Fine Art for my BA, so we didn’t have an immediate network of artists. It’s also nice for us to broaden and diversify the programme, to see what’s out there.

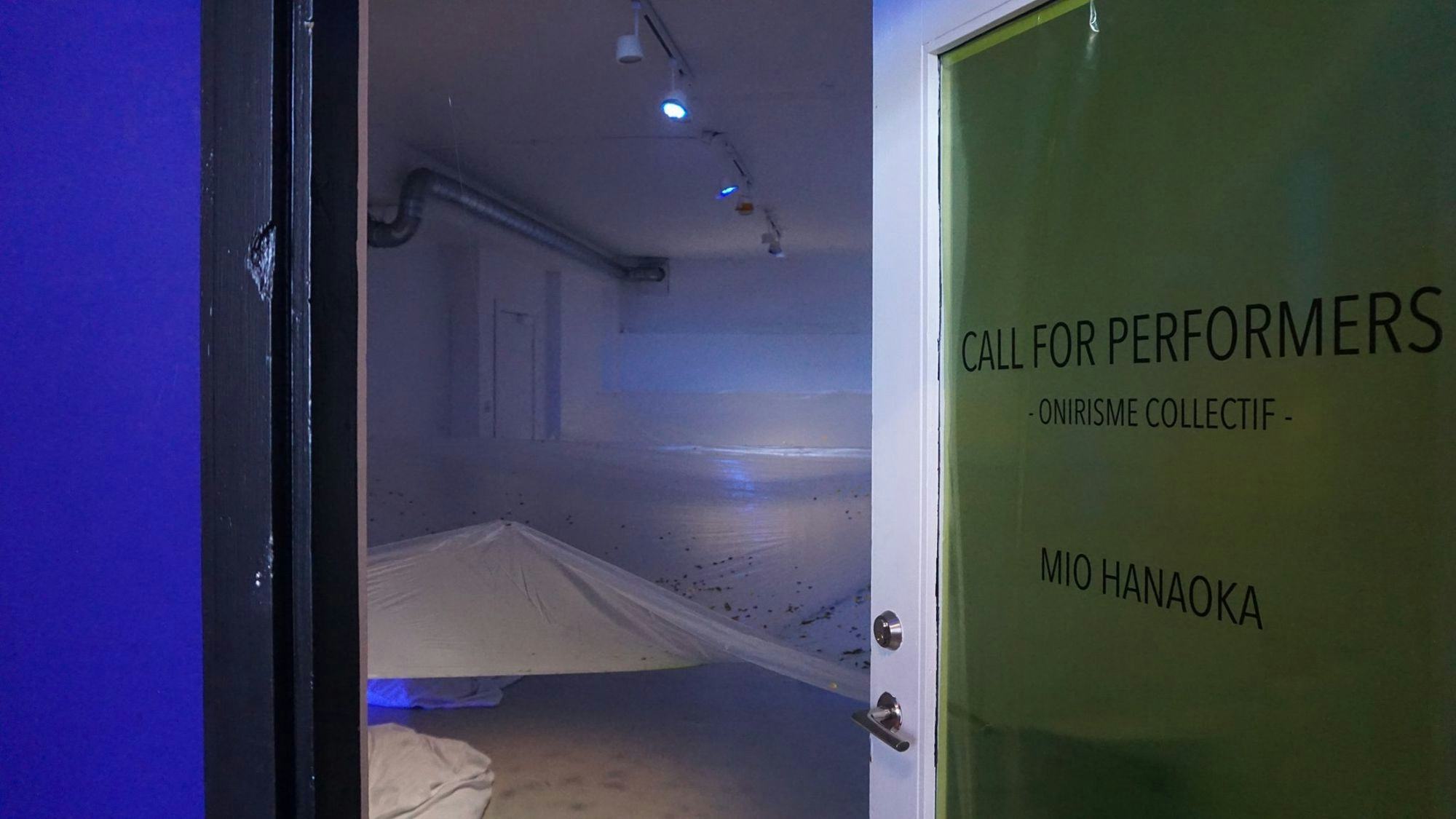

We select some artists ourselves, and each show is curated from our perspective, considering what we think is best for the gallery. Since we both come from theatre backgrounds, we are more interested in installations and performance than two-dimensional work. We’re also interested in seeing how people can transform the space, because it’s quite unassuming, and small.. It’s so amazing to see how artists can really change this little cave into something really spectacular.

Midpunkt

Why did you choose this particular space and decide to open a gallery here in Kópavogur?

We were living in Brussels at the time, and we had a desire to do something. We didn’t belong to any specific art scene there, but we opened up a little gallery in our home, and it ended up being only on Instagram, which was fun and weird. When we had to move back to Iceland, opening a gallery here was our immediate idea. We felt we wanted to open a space that was not in downtown, because there is a lot of art there already.

Since 2008, we’ve been talking about how things are always centered around 101, and how other people in other neighbourhoods are not confronted with artworks or performances, or the opportunity to just walk through art to your store in your neighbourhood. Although you don’t do it every day, or even every month, it’s still an option [if you live in the centre of town]. That was our aim—to move art closer to the people. I had a studio here in Kópavogur, and we were just hanging a lot in Hamraborg. At the time, we were living in Hafnarfjordur and it was easy to meet up here—Te & Kaffi had just recently opened, and if we had a meeting, people would come from Hafnarfjordur. We also moved here from Paris at the time, and this city-like space that Hamraborg is, felt almost like a new version of the outskirts of Paris. Really modern and ugly, uncomfortable but also beautiful in it’s own way. So, we fell in love with it. There was a gallery here run by other artists here, but it closed down. It was called Anarkía… and, so we knew about them and we were like ‘oh god, we need to take over the space, this is the only gallery here…’

One afternoon, over a lot of coffee, we thought about what we wanted to do and mapped out a plan—we sent it to Kópavogur and said ‘here’s our plan, let’s really see what can be done’. They were really interested in it, and immediately wanted to have a meeting and discuss how we were going to do it together. There is a lot of gentrifying happening in the area and it will keep transforming in the next few years, so they were interested in new ways to bring culture into Kópavogur that hadn’t been here before. During those meetings and discussions that were happening, we lost the space. So we thought, ‘okay, now we have kind of a yes, and we have a little bit of money’, so we went space hunting again. We walked around here, and knocked on some doors.

We were searching everywhere, but there was nothing free. And then we came by this building, and the man that owned this place at the time had just recently bought it to open a sound-system store. He was doing up the windows and I knocked on the door. I knew about the interiors because my mum and dad used to run an ice cream store in this space, and this was our larder, where we kept all the candy. I knocked on the door and I was like, ‘what are you doing with your downstairs space?’ He was like, ‘how do you know about that?’ Because the windows were blocked, and it wasn’t visible from the street.

The spaces down here are always like these crooked, strange things. My mum and dad were here almost 30 years ago. I would visit the space from the age of 12 to around 19 a lot, I worked in the ice cream shop. It has a really personal significance—I almost feel like it’s my second home. I always came here after school. So it kind of just all fell together, everything that we wished for, just happened.

The name of the gallery also took us over a month to brainstorm—it had to be something that has a broader meaning to us, and it had to embody something that feels like home. Something that we connect to—me and Snaebjorn. He is great with coming up with all different kinds of ideas. And then he said, ‘why don’t we just call it Midtpunkt?’ There was a bar in Brussels that we would always go to, it was really run down, really shabby, but it was an artist bar, they had performances there and you could meet people that you knew. We thought ‘it’s not miðpunktur.. it’s Midtpunkt—it’s actually Flemish!’

Let’s talk about a significant exhibition, one that you opened with or that surprised you in a certain way?

We opened Midpunkt with a collaboration with Cycle, a festival that finished in 2020. We were a bit lucky to open with them—it benefitted both of us, we had a place to host. We needed a good kickstart, and the festival put us on the map, so that people knew what’s happening here.

The exhibition was a video installation by Thurídur Jónsdóttir. It was participatory, so people could come inside, and they could sing into a microphone, and the video changed as they went through the space. I think for the hopeful art lovers and visitors to the space, it was quite playful. I knew that families were coming afterwards to the other exhibitions because of it—they were asking to revisit the installation because it was so much fun. That brings a little bit of a light in my heart—it was really nice to be a part of the festival, and we were honoured to be on the list of the venues, and it has also started a really nice conversation with culture houses in Kópavogur, so we are, kind of always collaborating. We try to plan a little bit in advance, so that our openings are the same as other galleries.

How have you structured the programming this year?

This year we are showing foreigners who live in Iceland. I wanted to have a new oasis, and show people that you can do art differently. There is not only one way to do it. Sometimes in small communities, there’s one direction that is funnelled, and that becomes the mainstream, and that’s the only thing that is allowed—that’s kind of sad. We want to see something that uses different techniques.

Miðpunkt

Can you talk about any shows that have surprised you or changed your expectations?

We did have one spontaneous show at the beginning of this year, we had an artist called Gígja Jónsdóttir, and I contacted her at the beginning of December and asked if she wanted to do something in January, and she said she had to think about it. It was a really quick turnaround, but she totally delivered, she changed the whole space with this really nice video work of her grandma and sister of her grandma, of all the women in her family—they were dying her hair pink. There’s 45 minutes where they are just dying her hair, cleaning it, and just the conversations are so nice. There were curtains hanging across the space, with a pink hue. I was surprised by that exhibition.

One other show that really surprised took place during the first summer we opened, in 2019. There’s an artist Bjarnadóttir … she is taking over an old slaughterhouse. I saw that they were having some performances there. We didn’t know what she was planning to do for the exhibition at Midpunkt—she was moving to this old house where her family lived, and nobody lived there anymore, and she said she wanted to create something from that space, and take things from there. We really had no idea what to expect, but she created magic! She changed the space into a really nice exhibition, where she hosted around 12 events over three weeks. She came to Kópavogur every week, for three days, and had an event everyday, morning meditations etc., it was really beautiful. The way she presented the art and created the space, and the whole atmosphere of the space really changed. It was really beautiful and so surprising, in a really good way.

Those kinds of events are really community building…

Yes, it was so interesting to come into an exhibition, where you have to sit down and have a meditation. You’re sitting inside a venue that you’re supposed to observe, but you sit down, and close your eyes and go inward, so it’s totally opposite of how you’re supposed to act in an art space. I think that’s also why it was really beautiful.

I could talk endlessly about Midpunkt, it’s my baby. My grandma said really nice things about the space. She’s been here a couple of times. I was talking with her about the Marshall House opening, and she was like ‘again, [deep breath] far away from me…’ And so, I think how a space is presented and where it is situated has a big impact. She really wants to go to the Marshall House, but she doesn’t see a reason to drive across town from one end to the other. If it was in her neighbourhood, she would probably go—so with Midpunkt being in Kópavogur, it gives the local community a closer interaction with art.

-icelandic-pavilion-2000x2667.jpg&w=2048&q=80)